Written by Julia Schulz

Biography

Lady Cecil (see fig. 1), born on April 25, 1857 in Diddlingon Hall, was the oldest daughter of William Amherst Thyssen-Amherst best known for his significant collection of Egyptian antiquities and manuscripts including the Amherst Papyri.1 Her growing up surrounded by Egypt’s past and several journeys with her family into the country increased her fascination with this rich culture and therefore her later occupation as an amateur archaeologist.2

jjjjjjjjjjj

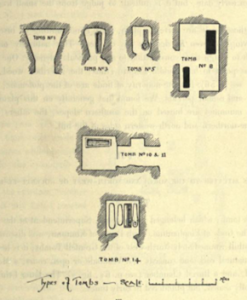

Fig. 2: The tombs at Qubbet el-Hawa.

In the winter of 1901/2 Lady Cecil and her family stayed in Aswan, part of the time in a camp on the western side of the Nile where, with permission of the Service des Antiquités3, Lady Cecil carried out excavations at Qubbet el-Hawa (see fig. 2).4 During this period, Cecil and her team investigated twenty-four mostly rock-hewn tombs, from different periods, which they discovered along the mountain.5 Due to her father’s relations and his support of Howard Carter’s and Flinders Petrie’s excavations in Tell el-Amarna, Lady Cecil connected with other prominent archaeologists like Gaston Maspero who at that time was the director of the Service des Antiquités. He visited her first dig at Qubbet el-Hawa and licensed an enlargement of the area to be excavated.6

The results of this first excavation proved to be very promising and therefore led to a second archaeological dig in 1904 during which eight more tombs were uncovered.7 Lady Cecil published her observations and results in the “Annales du Service des Antiquités de l’Egypte” of 1903 and 1905.8

The excavations at Qubbet el-Hawa (1901/2, 1904)

In her first report from 1903 (see fig. 3) Lady Cecil describes the discovery and excavation of twenty-four tombs to the southern, the northern, the north-western and the eastern side of Qubbet el-Hawa as well as on the north-eastern slope of the mountain above the ruined Coptic convent of St. George.9 They are situated in vicinity of the so-called “Grenfell tombs” which Cecil often uses as a geographical point of reference in her descriptions.10 The tombs date from the 5th, 6th, 7th, 19th and 26th dynasty and furthermore from the Ptolemaic, Greco-Roman and early Christian times. Most of these tombs date in the Old Kingdom and were reused in later periods.11 Some of them show signs of reoccupation in Roman times since they contain mummies, mummy masks, fragments of cartonnage casings and pottery sherds from that period.12

Discovered artefacts consists of many different object groups including coffins, beads, amulets and figurines but unfortunately much of the material remains were already partly or completely destroyed due to an infestation of white ants.13 Most of the finds were either retained by the Service des Antiquités or brought back to England by Cecil and her family were they became part of their private collection at Didlington Hall.14

These findings include pieces of papyri written in Demotic and cursive Greek, which Cecil and her team found in tomb 8. In tomb 9, they excavated an inscribed funerary stele and cartonnage with Demotic and Greek inscriptions on the rear side including the Greek name Pelias Paitos.15

Fig. 3: Plans of different tombs from Lady Cecil’s excavation report, published in 1903.

They moreover discovered a blue faience vase in tomb 19 and in the shape of a pilgrim bottle with a neck engraved like a lotus flower and two apes at the rim. A hieroglyphic inscription goes around the body of the vase reading “Ptah wishes the owner a happy new year”.16

The excavation team discovered, moreover, two coffins in tomb 21, belonging to a man and a woman of the 26th dynasty and decorated with coffin texts on the inside. The man’s coffin was almost completely destroyed by white ants and could not be saved wheras the woman’s coffin was in a far better state and could be retrieved.17 Both mummies had been covered with an elaborate network of beads as well as winged scarabs and Amenti figures.18

In the second excavation starting on the 17th February 1904, Cecil and her team continued work at the tombs on the north-eastern slope of Qubbet el-Hawa and subsequently on the eastern side south of the “Grenfell Tombs”. The overall eight tombs were also rock-hewn and could be dated to the Old Kingdom with reoccupation in later pharaonic and roman times.19 They discovered part of a limestone stele in tomb 28, dating to 12th dynasty, probably in the reign of Sesostris I.20

Lady Cecil managed, moreover, to buy three and a half of the overall ten Aramaic papyri belonging to a family archive from Elephantine.21 The papyri can be dated to the 5th century BCE under the reigns of Xerxes I, Artaxerxes I and Darius II.22 They contain the juristic documents of a family of three generations and provide valuable linguistic information about the older Aramaic and enrich our knowledge of the cultural and juristic circumstances of contemporary Jews living in Elephantine.23

- Bierbrier 1995, 14. Collection of Papyri compiled by William Tyssen-Amherst with Papyri dating from the Middle Kingdom until the Arabic period. Since 1912 in the possession of the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. (See <https://www.themorgan.org/search/collection/amherst%20papyrus > (Accessed 24.05.2021)). ↩

- This information and further details about Lady William Cecil’s life and the collection of her family are taken from the online blog of the British author Angela Cecil Reid who is a descendant of the female archaeologist herself, cf. <https://amhersts-of-didlington.com/well2.html> (Accessed 28.05.2021). ↩

- The permits and workers for the dig were organized by Howard Carter who was on of the European chief inspectors of the Service des Antiquités at that time. He encouraged Lady Cecil to undertake the excavation and his presence during the excavations in 1901/2 is also mentioned by her on several occasions in her excavation report (James 2012, 94; Cecil 1903, 62-64). ↩

- Cecil 1904, 3. ↩

- Cecil 1904, 4. For a more recent publication on the Qubbet el-Hawa see: E. Edel, Die Felsengräbernekropole der Qubbet el-Hawa bei Assuan, 3 vols. (Wiesbaden 1975). ↩

- Cecil 1903, 55; James 2012, 95. ↩

- Cecil 1905, 273. ↩

- See Cecil 1903 and Cecil 1905. ↩

- For further reading on the Coptic Monastery and its connection to St. George see V. B. Colmenero, S. T. Tovar, “Archaeological and Epigraphical Survey of the Coptic Monastery at Qubbet el-Hawa (Aswan)“, in: P. Buzi (ed.), Coptic Literature in Context (Rome 2020) 149-160, and the ostraca from the site edited by S. T. Richter in: E. Edel, Die Felsengräbernekropole der Qubbet el-Hawa bei Assuan, vol. 1 (Wiesbaden 1975) 518-522. ↩

- Cecil 1903, 60; 64. Cecil 1905, 279. ↩

- Cecil 1904, 4; Cecil 1905, 283. ↩

- See e. g. Tombs 7, 11, 13 in Cecil 1903, 53-57. ↩

- Destructions caused by white ants are often mentioned during Lady Cecil’s excavation reports, see for instance, the damage done to the religious wall paintings at the entrance to tomb 15, the only burial place that was decorated. Cecil 1903, 60. ↩

- The Amherst collection was sold after the family’s bankrupt in 1921 with the involvement of Howard Carter which caused a distribution of objects to different museums over the world (<https://amhersts-of-didlington.com/well1.html> (Accessed 28.05.2021)). ↩

- Cecil 1903, 54-55. ↩

- Cecil 1904, 5; Cecil 1903, 68. ↩

- The coffin is stored today at the Kalamazoo Public Museum in Michigan (KPM 32.316). It belonged to a woman called Bao-Bao (Bꜣw-bꜣwꜣ) and is the only Saite coffin with a clear provenance in the necropolis of Qubbet el-Hawa (Elias 1996, 105; 107). For further reading see the article by J. Elias, Regional Indicia on a Saite Coffin from Qubbet El- Hawa, in: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, vol. 33 (1996) 105-122. ↩

- Cecil 1903, 71. ↩

- Cecil 1905, 283. ↩

- The stele can be found in the Cleveland Museum of Art (CMA 21.1017) today (<https://www.clevelandart.org/art/1921.1017> (Accessed 26.05.2021)). For further reading see the article by L. M. Berman, The Stele of Shemai, Chief of Police, of the Early Twelfth Dynasty, in The Cleveland Museum of Art, in: Studies Simpson (Boston 1996) 93-99. ↩

- Cecil’s papyri are part of the Bodleian Library today while the other papyri were acquired by Robert Mond and were given to the Cairo Museum (Mode 1907, 305). ↩

- 3rd, 4th and 6th king of the 27th dynasty, ca. 486/85-405/04 BCE (Beckerath 1999, 287). ↩

- Mode 1907, 305. For further reading see the article by R. H. Mode, The Assuan Aramaic Papyri, in: The Biblical World, vol. 29, no. 4 (1907) 305-309. ↩