Written by Julia Schulz

Biography

Amelia Edwards (see fig. 1) was a British author and Egyptologist born in London, on June 7, 1831. She wrote poems and romance novels from an early age on and illustrated them herself. After a short interlude the music industry, Edwards became a full-fledged author and wrote for several daily and weekly newspapers including the “Morning Post”. 1

Edwards enjoyed exploring different countries including Egypt which she visited in 1873-4 and 1877 accompanied by her friend Lucy Renshawe. In Cairo they hired a dahabiyah and sailed up the Nile until Wadi Halfa. Edwards made notes of everything and after her return to England she published her observations in the book “A Thousand Miles up the Nile (1876)”.2

Edward’s Connections and the Egypt Exploration Society

Egypt simply fascinated her, so that country and culture became recurring topics in the about 100 articles she published until her death in 1892.3 In these and her major work “A Thousand Miles up the Nile” Edwards mixed her own experiences and research with scholarly knowledge from which she benefitted by her exchange with Egyptologists and Archaeologists such as Samuel Birch, Reginald S. Poole4 , Joseph Bonomi5 and especially Gaston Maspero.6

However, Edwards not only contented herself with writing about Egyptian culture, she also became active in preserving it. After she had witnessed the neglect and vandalism of ancient Egyptian monuments by visitors, she established a British organization for scientific excavations in Egypt. This was to ensure the careful treatment of ancient objects and protection on site as well as to prevent the decontextualization of those artefacts by excavators with no scientific objective. This led to the founding of the Egypt Exploration Fund (later called the Egypt Exploration Society) in 1882. As an honorary secretary for the EEF, Edwards facilitated the careers of many well-known Egyptologists over the years such as Flinders Petrie and Francis Llewellyn Griffith.7

A Thousand Miles up the Nile

Edwards begins her account of the First Cataract by describing the island of Elephantine and its position between the “Libyan shore”, for which she mentions a skeikh’s tomb and the “Arabian shore” with its Moorish architecture.8 She describes Elephantine as “(…) rugged and lofty to the South; low and fertile to the North; with an exquisitely varied coast-line full of wooded creeks and miniature beaches,(…)”.9 Edwards mentions two modern Nubian villages on the island and the remains of an ancient city. The two temples which Edwards dates to the reign of Amenhotep III10 had already been destroyed in 182911 in the course of building new barracks and were therefore not accessible for her and her team. She furthermore refers to a ruined gateway from the Ptolemaic period and a sitting statue of king Merenptah.12 Those together with the ruins of a Roman quay nearly opposite of Aswan are the only archaeological remains of interest for Edwards on the island.13

At the southern end of the island next to rubbish heaps with bleached bones and human skulls they found piles of parti-colored potsherds inscribed in Greek. At that time, she failed to identify them as scientifically relevant but nonetheless took a few as souvenirs.14 Later, in her travel report, Edwards regrets the lost opportunity for research since, if she recognized the historical and philological value of these sherds earlier, she would have acquired more ostraca. In her report she relates her findings to ostraca from the same spot which were at the time of her visit on Elepantine already in the British Museum and studied by Dr. Birch15 The British ostraca are mostly tax-receipts dating to the Roman Period but some of them were also written in Demotic, Hieratic and Arabic which at that time had not yet been translated or published. She characterizes them as documents concerned with business transactions and private letters.16 Edwards surmises that the ostraca she saw at Elephantine probably hat comparable contents.17

Between Elephantine and Aswan

After arriving on the mainland by boat Edwards and her companions continued their journey on camels. Before leaving for Philae they visited the Fatimid cemetery and the quarries that lie behind the town before riding into modern Aswan one more time.18 At the cemetery she describes small mosques, scattered tombstones and “commemorative chapels dedicated to saints and martyrs elsewhere buried”.19 The gravestones were mostly rounded at the top and entailed inscriptions about which Edwards writes that they are of “the Cufic character”.20 The team continued towards the stone-quarry of Aswan with its monolith as their main object of interest. The unfinished obelisk which still lies in the quarry has visible tool-marks of the workmen and if it had been completed it would have been the tallest obelisk ever manufactured. In her report Edwards goes into details about the process of quarrying by describing how the blocks were split off, which tools were used and which techniques.21

Passing the outskirts of Aswan, they found a small, half-buried Ptolemaic temple. Edwards could discern traces of color and mutilated bas-reliefs, but the structure was not accessible, and the travelers rode on without further inspection.22

Philae

Between Aswan and Philae, Edwards and her company made halt in Mahatta which she describes as “by far the most beautifully situated village on the Nile”.23 It is the residence of the principal sheikh and serves as a port for trade between Egypt and Soudan (see fig. 2).

ffffffff

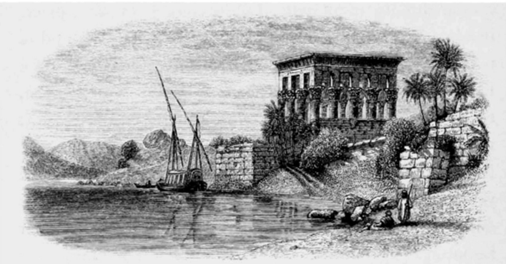

Edwards describes Philae as still perfectly intact and framed by rocks on both sides. 24They approached the island from its southern end because here was its original landing-place. The empty socket of the so-called Philae obelisk and another obelisk remaining in situ can be seen here.25 From there, the travel group first passed under the so-called “Pharaoh’s Bed” (see fig. 3), a little roofless temple which as Edwards emphasizes was the object of many paintings and photographs taken at Philae.26 She mentions a great temple with irregular shapes and angles and between the colonnades of the courtyard the brick foundations of a Coptic village which Edwards dates to the early Christian time. The inner court is also of an erratic quadrangular shape and framed by an open colonnade on the East and a chapel in the West, decorated with Hathor-columns at its front side. Edwards states that the chapel dedicated to Hathor and the birth of her son Horus was built by Ptolemy Euergetes III27 and that Jean-François Champollion named it mammisi.28

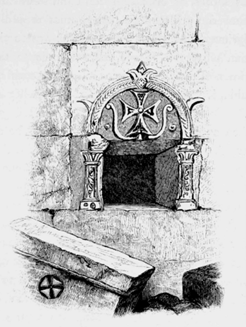

After passing the second propylon, the travel group finds itself in the portico which is painted and open in the center like a Roman atrium.29 Edwards reports that “a Greek cross cut deep into the side of the shaft stamps upon each pillar the seal of Christian worship”.30 The portico was turned into a chapel dedicated to St. Stephen, with a rough-hewn niche in the Eastern wall and an overturned credence-table. Both the niche and the credence-table were decorated with Byzantine carvings and a cross (see fig. 4).31 A Greek inscription on the wall says: “This good work was done by the well-beloved of God, the Abbott-Bishop. Theodore”.32

For the Northern end of the island Edwards mentions a small Coptic Basilica which was built with masonry from the Southern quay and blocks from an older structure from Philae.33

Edwards also describes a copy of the Rosetta Stone inscriptions which were first discovered by Karl Richard Lepsius in 1843 and can be found on the outer wall of an adjoining small chapel. At the time of her visit the preservation of the inscription was in good conditions, although as she remarks the Philae version was incomplete. The Greek part was missing, and Edwards surmised that this omission was intentional.34

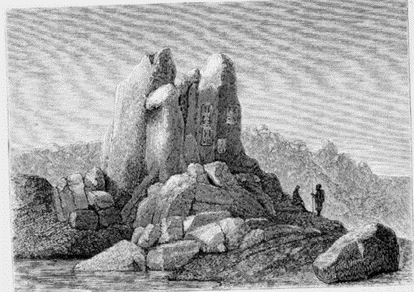

At the end of her account of Philae Edwards illustrates the surroundings of the island. On the Western side she draws the island of Biggeh which is divided from Philae by a narrow channel. The modern village of Biggeh is built on the remains of a Ptolemaic Temple of which only scattered parts could still be seen.35 Edwards describes, moreover, a huge, inscribed monolithic rock called by the Arabs the “Pharaos’s throne” (see fig. 5). It lays by the water’s edge opposite of Philae and as Edwards adds, was mentioned by all kinds of earlier visitors such as kings, conquerors, priests, and travelers like Edwards herself.36

- Manley, D., Edwards. Amelia Ann Blanford (1831–1892), in: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2015). Online available under https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-8529 (Accessed: 03.11.2021). ↩

- See above, Manley 2015. ↩

- Manley 2015. ↩

- Both Birch and Poole were working for the British Museum at that time and helped her with historical and archaeological questions. Birch translated hieratic and hieroglyphic inscriptions for her publication, and she was taught how to read and write hieroglyphs herself (Edwards 1890, viii; xiii; Lanoie 2013, 151, Manley 2015). ↩

- Bonomi was an artist and curator of Sir John Soane’s Museum of Antiquities. Edwards contacted him with specific questions concerning the interior temple of Abu Simbel (Lanoie 2013, 151). ↩

- Edwards and Maspero had frequent correspondence in which Maspero made many comments and notes on passages of Edwards book, for more information see Dawson, W. R., Letters from Maspero to Amelia Edwards, in: Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, vol. 33 (1947) 66-89. ↩

- Manley 2015. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 257. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 267. ↩

- 9th ruler of the 18th Dynasty, 1388-1351/50 BCE (Beckerath 1999, 286). ↩

- The temples were still intact when Belzoni visited the island in 1815 but were demolished by the time Champollion visited in 1829 (Edwards 1890, 268). ↩

- Edwards 1890, 267-8. 4th ruler of the 19th Dynasty, 1213-1203 BCE (Beckerath 1999, 286). ↩

- Edwards 1890, 271. ↩

- Edwards does not mention where those sherds ended up and there seem to be no other written records about them. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 268-9. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 270. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 269. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 275; 286. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 278. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 278-9. For a recent study of the cemetery, cf. the forthcoming publication by Speidel; Nogara 2021. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 279-80; 282-83. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 283. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 299. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 307. ↩

- The obelisk was transported by William John Bankes to his estate in Dorsetshire in the 1820s. It held hieroglyphic and Greek inscriptions and helped Champollion deciphering the hieroglyphs (Edwards 1890, 331). ↩

- Edwards 1890, 308. ↩

- In her publication Edwards writes Ptolemy Euergetes II but according to Beckerath’s chronology Ptolemy Euergetes is the 3rd ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty, 246-221 BCE (Beckerath 1999, 288). ↩

- Edwards 1890, 309-11. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 317; 319. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 320. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 320-21; 326. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 326. This Theodore is mentioned in another inscription but there is no further information about him. There are many more of these kind of inscriptions across the walls, if Coptic all followed by a cross (Edwards 1890, 326-27). ↩

- Edwards 1890, 320. Edwards also mentions two large convents which she saw on the Eastern bank up the Nile (Edwards 1890, 320). ↩

- Edwards 1890, 311-14. Edwards’ reason for this assumption is a similar inscription with missing Greek paragraph which is a part of the foundation at the easternmost tower of the second propylon. She suggests that the priest of Philae might have disliked the Greek language (Edwards 1890, 315-16). ↩

- Edwards 1890, 338-39. ↩

- Edwards 1890, 340-41. ↩