a. Passage of the First Cataract.

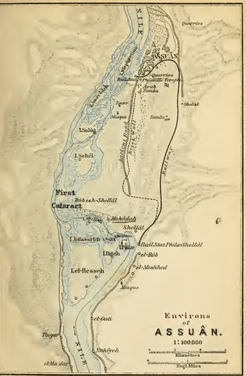

The First Cataract (Arab. Shellâl, from the earlier form Djéndal) lies between Assuân and Philae (see fig. 1). It must be passed by all who desire to proceed in their own dhahabîyeh to Wâdi Ḥalfah and the second cataract. When the river is high the passage is quite without danger, and though it is more difficult at later periods of the year, nothing more serious need be feared than some slight damage to the boat. A considerable amount of time, however, is consumed by the passage, except under favourable circumstances and when the river is at its highest. Including the necessary preparations, 2-3 days must be set aside for the passage; and a carefully drawn-up contract (p. xxii) will be found here especially useful. Travellers who have previously arranged with their dragoman to be conveyed to and from Wâdi Ḥalfah for a fixed sum including the passage of the cataract, will come off best. Those who have no such arrangement must come to terms with one of the shêkhs of the Shellâl or chiefs of the cataracts. With a reliable dragoman the matter may be arranged in ten minutes, but otherwise (too frequently the case) difficulties are sure to arise. The boat will be objected to as too high, too weak, or two large, the water will be described as too low, or the wind (which must certainly be taken into the calculation) as too gentle; but none of these objections should be listened to, if the dhahabîyeh has been originally hired to ascend beyond the cataract. Energy and bakshîsh will overcome difficulties. If the dragoman prove [sic] too recalcitrant, the traveller should threaten to proceed to Wâdi Ḥalfah by camel or by a dhahabîyeh from Philae, and to bring an action for damages against the dragoman on his return to Cairo. That will generally produce an effect; but the action for damages should not, in the interest of future travellers, be allowed to remain an empty threat. Dhahabîyehs may be hired above the cataract, but they are inferior and dear. The cost of ascending the rapids varies from 4 to 6l., according to the size of the boat, to which a bakshîsh of at least 2-3l. must be added. This amount of bakshîsh must be paid because as many as 50 or 60, or even, when the vessel is large and the water low, 100 men are required to tow a dhahabîyeh up the rapids. Travellers may remain on board during the operation if they choose, but as the passage takes several hours, they lose much time.1

Since the construction of the railway from Assuân to Philae, and owing to the disturbances caused by the Beduins, the journey between the cataracts is now very seldom made by dhahabîyeh; and the ascent of the rapids by a passenger-boat is quite exceptional.2

The descent of the foaming rapids is much more interesting. Those who are very cautions may perhaps cause their more precious possessions to be transported past the cataract by land; but serious accidents almost never occur, though the wrecks of some dhahabîyehs on the banks prove that the descent is not absolutely without danger. An excellent view of the passage may be obtained from a rock on the bank (Bab esh-Shellâl, p. 278).3

Passengers by Cook’s steamers are conveyed down the rapids to Assuân in a rowing-boat for 4s. a head, an interesting trip, not wholly devoid of danger. A halt is made before the chief rapid, in order to view the natives descending it on trunks of trees. As usual the visitor is harassed by demands for bakshîsh. The voyage is then continued through smaller channels, and at dangerous points, the boat is secured by ropes. See description of a trip of this kind on p. 279.4

The dhahabîyeh ascends in untroubled water as far as the island of Sehêl. There it is surrounded by the dark, sinewy, and generally most symmetrical forms of the Arabs who are to tow it through the rapids. Some come on board under the direction of a shêkh, while others remain on the bank. At first the dhahabîyeh passes the beginning of the rapids comparatively easily, but by-and-by, ropes are fastened to the mast, and the severe struggle with the descending current begins. Some haul on the ropes from the bank, others guide the course of the vessel with poles from on board, and others in the water keep it upright or ward it off from striking on sharp rocks in the river-bed. Old men, young men, and boys rival each other in the most exhausting activity, that seems almost frantic, from its never-ceasing accompaniment of shouts, cries, and chants. Every saint in the calendar is invoked, especially the beneficent Saꜥîd, who is believed to render especially effective aid in sudden dangers. At the most difficult point, the Bab el-Kebîr (p. 278) boys, for a small fee, will plunge head-first into the stream, to reappear astride pieces of wood below the boiling surf, through which they swim with marvellous skill. If the work is not accomplished before sun-set, it is left unfinished till next morning. — It may be remarked that the Egyptian government contemplates widening the channel and introducing fixed regulations for the passage. — The time occupied in taking the dhahabîyeh through the rapids may be advantageously turned to account by the traveller by first inspecting the cataract from the bank and then, by proceeding by land to Philae, where he should pitch his tent or take up his abode in the Osiris room (p. 295). The most necessary articles can easily be transported through the rapids by a few of the sailors in the small boat. The dragoman will arrange the new household with the assistance of the cook and the camp-servant. A few days spent at Philae, especially at full moon, will not easily be forgotten. — It is not advisable to bring the dhahabîyeh as far as the island of Sehêl and to visit Philae thence, because there are no donkeys to be there obtained.5

b. From Assuân to Philae by land.

Railway in ½ hr., fare 5 piastres; one train daily (1891) to Shellâl at 8.30 a.m., returning at 11 a.m. — The Ride to Philae takes t1/2 hr.; excellent donkeys at the landing-place. Rich inhabitants of Assuân spend large sums upon their riding-asses; spirited Abyssinian donkeys, if they are also handsome, cost from 30l. upwards. — The inspection of the objects of interest of Assuân occupies 3-4 hrs.6

The route leads past the Post Office into the town, then turns to the right (leaving the Bazaar on the left) and follows the telegraph-wires across a (5 min.) bridge over the railway to Philae (Shellâl). The Ptolemaic Temple lies a few minutes to the left, below (see below). Thence we proceed straight on to the Moḥammedan Tombs, passing on the way the graves of an Austrian and of a sailor of the British ship ‘Monarch’ (Dawe; d. 1884). The Quarries are reached from the Ptolemaic temple by continuing straight un for a few minutes, then turning abruptly into the desert path, which soon brings us in sight of tall blocks of stone, behind which is the quarry (p. 276). The obelisk lies 10 min. to the right of the above-mentioned European graves.7

1. The Ptolemaic Temple.

The attentive observer will notice many blocks and slabs with hieroglyphic inscriptions built into the houses of Assuân. In the station also there is a block of granite with the name of Tutmes III., possibly dating from a temple at Syene, on which Khnum, lord of Kebu (see fig. 2), within Abu (Elephantine) is named. Several attractive houses, one belonging to a wealthy Jew, form a kind of suburb here.8

To the left of the road lies the small TEMPLE, founded by Ptolemy III. Euergetes and adorned by Ptolemy IV. Philopator, but never entirely completed. On the left of the Facade is Euergetes I. and his wife Berenice II., before Isis in Sun (Syene). Isis is named conductress of the soldiers, because the frontier-town and its neighbourhood were strongly garrisoned from very early times as well as under the Romans. (Under the Romans the Cohors Quinta Suenensium was stationed at Contra Syene, the Cohors Sexta Saginarum in the Castra Lapidariorum, on the E. bank to the S. of Syene, the Cohors Prima Felix Theodosiana on Elephantine, and the Legio Prima Maximiana on Philae.) Next appears Ptulmis, son of Euergetes, otherwise Philopator, before Khnum, Sati, and Anuke, who each wears his special head-dress. On the right side of the facade is Euergetes I., before Sebek and Hathor, and offering incense before Osiris Unnofer (the good), Isis, and the child Horus.9

On the Inner sides of the two doors leading to the antechamber with its two square columns, and on the inner side of the door to the adytnm. are inscribed stirring Hymns to Isis-Sothis, to whom apparently the little temple was dedicated. To the left, on the latter door, are e.g. the words: ‘Thou hurlest forth (sati) the Nile, that he may fertilize the land in thy name of Sothis, thou embracest (ank) the fields to make them fertile in thy name of Ankht. All beings on earth exist through thee, through thy name of Ankht (‘the living’).10

Unusually thick pillars in the first and largest chamber of the temple support flat Greek abaci, upon which rests a broad but flat architrave. Completed inscriptions are to be found only on the partition-wall between the sanctuary and the preceding hall, on the entrance door, and at a few points on the inner walls.11

Near the temple is a rock-inscription of the time of Khu-en-aten. To the left appears the sculptor Men, before a sitting figure of Amenhotep III. perhaps carved by himself, to the right is a son of Men named Bek, making an offering. Bek is also a master-sculptor of the sun, whose beams radiate in the form of hands. The cartouches of Khu-en-aten are defaced.12

2. The Arab Cemeteries.

A brief ride brings us to an Immense number of Arab graves, lying in the midst of the desert, each marked by a rectangle of unhewn stones, and a slab bearing an engraved inscription. Many are covered with a pall of yellow sand. The earliest of the hundreds of Epitaphs exhibit the venerable Cufic character and date mostly from the 9th and 10th cent. A.D. A few are older and many are more recent. The inscriptions usually give the name of the deceased and the date of death. Texts from the Koran are not uncommon, in spite of the Prophet’s express command that the name of God and passages from the Koran should never be placed upon tombstones. The tombs of the richer dead are small domed erections. On the summit of the hill to the right of the road are some large mosque-like Cenotaphs, dedicated to famous saints, such as the Shêkh Maḥmûd, the Shêkh ꜥAli, our lady (sitte) Zeinab, etc., whose memory is celebrated by festivals on their birthdays, etc.13

3. The Quarries (Arabic Maꜥadîn).

About 1/4 hr. beyond Assuân we quit the road and turn to the E. (left). In a few minutes more we reach the verge of a hill, on which blocks of granite are scattered both singly and in heaps. A moderately lofty cliff beyond shows manifold traces of the industry of the ancient builders, who, from the erection of the pyramids to the time of the Ptolemies, drew their supplies of granite from the quarries of Syene. Almost all the granite pillars, columns, architraves, roof-slabs, obelisks, and statues that we have hitherto seen in Egypt, hail from this spot.14

Syenite owes its name to the early Greek form of the name of Assuân (Syene), although the stone here found is far too poor in hornblende to be reckoned true syenite at all.15 Hartmann describes it as follows: — The granite, which interrupts the sandstone at the cataracts of Assuân, is of a reddish hue, caused by bright rose-coloured orthoclase. It contains a large proportion of translucent quartz, yellow, brownish, pink, and black mica, and only a little hornblende. Huge coarse-grained masses of this composition are here found and also hard line-grained masses, containing much red felspar, but little quartz and very little mica. Veins also occur rich in dark mica and greenish oligoclase, and containing a little pinite; and finally veins of a dark green diorite, in which the proportion of hornblende is much greater than that of albite’. The glaze on the rocks of the cataracts is noticed on p. 279.16

The diligent hands of the stone-cutters of the Pharaohs have left distinct traces behind them. The method in which the blocks were quarried in tiers may still be distinctly seen on a cliff facing the N., about 8min. to the N.E. of the town. The skill with which huge masses were handled and detached without injury from the cliff to which they belonged, is absolutely marvellous. The certainty of the process adopted is amply vouched for by the fact that obelisks were completely finished on three sides before they were finally detached from their native rock, this final operation being probably accomplished with the aid of net wedges. Such an Obelisk, still attached to the rock, may be seen about 1/2 M. to the S. of the town and about as far to the E. of the Nile. It is not easily found, as it is frequently more than half-covered with sand. At its broadest part this obelisk measures 10 1/2 ft.; its length is 92 ft. (72 ft. cut out), not reckoning the pyramidal top, which has already been hewn. The economy of material on the part of the stone-cutters is noteworthy.17

In the quarry near the road and visited by all travellers, is a huge Block of Rock, from which the mason has begun to hew both a roofing-slab and a column. Here we clearly perceive that the ancients well understood how to disintegrate the granite with borers and to split it with wedges. Numerous holes were made in a fixed line (probably with the help of draw-boring), the damp wooden wedges were driven in, and in this manner tolerably even fractures were obtained. The art of splitting the stone by heat was also understood.18

The Chapel transported from Elephantine (i.e. Assuân) to Sais by Aahmes (26th Dyn.) was especially celebrated, and is mentioned by Herodotus (II, 175). It consisted of a single block and its transport occupied 2000 men for 3 years. It is said to have been 21 ells long, 14 broad, and 8 high, outside measurement; and 18 5/6 ells long, 12 broad, and 5 high, inside measurement. It had to remain outside the temple at Sais, on account of its size and weight. Still more striking, in point of weight at least, were the Statue of Ramses II. transported hence to the Ramesseum (p. 162), and a stone Chapel, seen by Herodotus (I, 155) at Buto. The latter was cubical in form and measured 40 ells each way; and it has been estimated that its weight must have been about 7000 shipping-tons, or more than twice the burden of a large East Indiaman.19

4. The Ancient Road and the Brick Wall.

We turn to the right (W.) from the quarries and follow the broad sandy road leading S. to Philae. The desert has a wonderful preserving virtue. If the road along which the traveller now rides were practicable for carriages, Strabo’s description would still fit it in every point. ‘We drove’, writes the ancient geographer, ‘from Syene (Assuân) to Philae, through a very flat plain about 50 stadia long. At many points all along the road, and on both sides, we saw the rounded, smooth, and almost conical blocks of dark, hard rock, resembling Hermes-towers, from which mortars are made. Smaller blocks lie upon larger ones, and support others in their turn; here and there were isolated blocks’, etc. — To this we need only add that pious pilgrims and wayfarers have chiselled their Names and short Inscriptions on many of the above-mentioned blocks. Princes, dignified priests, and warriors, have travelled this way, as far back as the times of the Amenemhas and Usertesens. Down to a late period pilgrims were in the habit of placing inscriptions on these stones, accompanied with the representation of the soles of the feet.20

Among the more noteworthy of these Inscriptions are a short one of the fourth year of Usertesen I. (see fig. 3), and a longer one of the fifth year of Amenhotep III., in which the king is likened to a fierce lion that seizes the Kushites in his claws. A Stele also, of the second year of Ramses the Great, shows on the left Ammon and on the right Khnum presenting the shopesh or sword of victory to the king, who grasps a negro by the hair. Many other ancient reliefs and inscriptions will be found by the careful seeker, both along this road and beside the Nile in the direction of and beside Assuân.21

By-and-by we perceive considerable fragments of a high Brick Wall, built to protect the road from the attacks of the Blemmyes (p. 302) and also perhaps from the shifting sand. Strabo, curiously enough, does not mention it. It first appears to the right (W.) of the road, crosses it twice, remains then on the E. side, and ends on the flat bank opposite Philae. It is 6 ft. broad, and at some places 13 ft, high.22

As this curious erection is almost entirely destroyed or covered with sand in the neighbourhood of Assuân, and as there are also other points of interest on the land-route to Philae (the inscriptions are most numerous near the island), no one who has a reasonable time to devote to the region of the first cataract, should fail to traverse this route once at least. The view of Philae, as the traveller approaches the end of his journey, will never be forgotten.23

c. Route partly through, the Desert, partly beside the Cataract.

This route is recommended to those who have arrived by steamer and have time to go to Philae and back once only. The return to Assuân is usually made (when there is moonlight invariably) after sunset, in which case, however, the traveller follows the desert-route all the way and sees nothing of the cataract. The rocky nature of the river-bank renders it impossible to skirt the stream during the first half of the distance from Assuân to Philae. After visiting the quarries, therefore, we follow the above-described desert-route for about 1/2 hr. towards the S., then enter a path diverging to the right (W.), which brings us in about an hour after quitting Assuân to the rocky bank of the river, whose hoarse roar is heard for some time before. Hence we are conducted to the rocks known as the Bibân esh-Shellâl, or ‘gates of the cataracts’, that with the largest fall being known as Bâb el-Kebîr or ‘great gate’. Here we may be fortunate enough to see a boat guided through the rapids; but in any case there are always naked young Nubians ready to plunge into the river and allow themselves to be carried down by the foaming stream, either astride of a tree-trunk or floating unsupported in the water, in the manner described long ago by Strabo. The air of course resounds with shouts and requests for bakshîsh. Those who expect to see a cascade like the falls of the Rhine at Schaffhausen will be disappointed. The foaming and impetuous stream makes noise enough as it dashes through its rocky bed, but there is nothing here in the shape of a regular waterfall. Yet all the same, especially when one beholds the placid surface of the river to the S. of Philae, one can sympathize with the question of the linen-clad Achoreus in Lucan: ‘Who would have supposed that thou, Oh gently-flowing Nile, wouldst burst forth with violent whirlpools into such wild rage?’ When the river is high all the rocks in the bed of the stream are under water; but in February and March even the smaller rocks are visible. Inscriptions are found on many of these, and on all the cataract-islands, twenty in number. The smooth glaze, like a dark enamel, which covers the granite- rocks between this point and Philae will not escape notice.24

A similar effect was noticed by Alexander von Humboldt at the cataracts of the Orinoco. ‘The granite of Assuân’, says R. Hartmann, ‘like that at the southern cataracts, etc., is distinguished by the remarkably rounded shape of the blocks. These have surfaces as smooth as glass, and are of a black hue, glistening in the sun, like the flat surface of a well-used smoothing-iron. The almost spherical shape seems to be due to the attrition of the detritus washed down by the stream. The dark colour, which only penetrates a few lines, as is easily seen in detached fragments, is caused by protoxide of iron according to Russegger, or by silica according to Delesse, precipitated on the stone by the Nilewater’.25

A few yards to the S. of the cataract lie the pleasant villages of Mahâdah and Shellâl, shaded by palms and sycamores. In Mahâdah huge piles of dried dates lie in the open air, brought hither from Nubia for transport to Egypt. At this point begins the passage of the rapids downstream; and boats (or dhahabîyehs for large parties) may be hired here, if desired, for the safe voyage to Philae through a picturesque rocky landscape. A bargain should be struck before the boat is entered. A small boat costs 10 piastres by tariff; a dhahabîyeh not less than 10 fr. The boatmen demand much larger sums at first.26

Descent of the Cataract in a small boat. This expedition can hardly be recommended, for even when the river is full it is not un- attended with danger. H. Brugsch and Ebers both accomplished it. The latter records that he looks back upon the experience not without pleasure, especially on account of the extraordinary skill and presence of mind of the cataract-re’îs who steered. He describes the trip as follows. ‘I had two of our own sailors on board, one able-bodied, the other a Nubian little more than a boy. The old cataract-re’îs was at the helm. The roar of the cataract was heard beyond the village of Shellâl, and became louder every minute as we proceeded. The rocks and stones in the riverbed are reddish brown, but wherever they have been washed by the stream and then dried by the scorching sun of this latitude, they glisten like the black surface of an evaporating pond. Behind and before, to the right and left, above and below, I saw nothing but rocks, little pools, and the blue sky; while my sense of hearing was as though spell-bound by the roar of the waters, which as soon as the keel of the boat approached the rapids proper, lifted up their voice as loud as surf lashing against a rocky coast in a storm. Then followed some minutes of the most intense exertion for the crew, who cheered and encouraged themselves by continual invocations to helpful saints, especially to the holy Said, the rescuer from sudden dangers. With each stroke of the oars broke forth a ‘ya Said’ (O Said) or ‘ya Mohámmed’ or ‘God is gracious’; while the arms wielding the oars dared not relax their strength, at it was essential to keep in the middle of the rapids in order to avoid being hurled against the rocks. The Arab, who guided the boat, was a sinewy old man over sixty years of age, who sat with his long neck craning forward so long as we hovered in danger, and who, with his eyes sparkling with intense excitement and his lean bird-like face, looked like an eagle on the look out for prey. All went well at first. Only a man and boy, however, were rowing on the left side, while two men were rowing on the right. As we quitted the second rapid and were entering a different channel, the sailors on the left side had to row with all their strength; that, however, proved inadequate and the stream swept the boat round, so that the stern was foremost. This was the culminating point of the passage. The re’is without losing his presence of mind for an instant, guided the helm with his foot, while he assisted the rowers with his arms, turned the boat round once more, brought it into the right channel, and finally into the less rapid part of the Nile, and so to Assuân. The entire passage lasted 42 minutes.27

From Mahâdah to Philae the crooked road skirts the bank of the river. The village-children pursue the traveller, begging for bakshîsh. When the path, covered with granite-dust, grows narrower and begins to lead over smooth granite, the traveller should dismount. The curiously-shaped rocks in the bed and on the bank of the Nile bear numerous inscriptions. Some of them look as though they had been built up out of artificially rounded blocks. These forms seem to have struck the ancient Egyptians most forcibly, for in the relief of the Source of the Nile at Philiae (p. 294) — one of the few representations of landscape in Egypt — the river-god crouches under a pile of blocks like these. In 25 min. we reach a small plain and obtain a charming view of Philae, the most beautiful spot on the Nile, and the goal of travellers who do not wish to go on to the second cataract. The small plain above-mentioned, to the E. of the island, is shaded with handsome sycamore trees, near which is a long low building of a semi-European appearance, with battlemented roof. This is the deserted station of the Roman Catholic missionaries, who hence founded settlements in Central Africa, all of which, however, including finally that at Khartûm, have been abandoned. The walled island, surrounded by clear smooth water, presents, with its imposing temple, graceful kiosque, and flourishing vegetation, a beautiful contrast to the rugged, bare and precipitous rocks that bound it, especially on the N. and W. To the N. a massive double rock, with the name of Psammetikh II. conspicuous upon it, towers above the rest; to the W. rises the rocky island of Bigeh (p. 297), with numerous monuments and inscriptions. The ferry-boat is to be found at the village of Shellâl. Between the railway-station of Shellâl and the Nile is a fine palm-grove, with the tents of the Egyptian troops under British command. The handsome dhahabîyeh near the bank is the residence of the commandant. Breakfast may be obtained on board, but those who come by rail are recommended to bring their provisions with them from Assûan.28

- Baedeker 1892, 272. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 273. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 273. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 273. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 273-4. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 274. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 274. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 274-5. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 275. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 275. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 275. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 275. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 275-6. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 276. ↩

- This curious fact is explained by Prof. Zirkel as follows. The term Syenite, which occurs in Pliny, was first employed in a scientific sense by Werner in 1788, who applied it to the characteristic stone formed of orthoclase felspar and black hornblende, found in the Plauensche Grund, in Saxony. Thenceforth that mineral was accepted as the typical syenite. Wad subsequently proved that the stone quarried at Syene was not syenite at all, i.e. that its formation was quite different from that of the rocks in the Plauensche Grund. When Rozière discovered true syenite on Mount Sinai he proposed to alter its name slightly and to call it Sinaite, a suggestion, however, which has never been adopted. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 276. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 276-7. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 277. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 277. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 277. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 278. These have been copied by Flinders Petrie and Griffith, and published by the former in his ‘Season in Egypt’ (1883). ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 278. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 278. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 278-9. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 279. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 279. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 279-80. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 280. ↩