“26 1/2 M. Steamboat in about 6 hours.

The W. side of the narrow river-channel is barren, while on the E. side there is only a narrow strip of cultivated land. Dark-skinned, nude Arabs of the tribe of the ‘Abâbdeh (p. 253) here and there work a water-wheel. Occasionally a crocodile may be seen on the bank; but travellers who ascend only to Phila are rarely gratified with a sight of one of these reptiles. — Darâwi, a station of the mail-steamer, on the E. bank, marks the limit of Arabic. Here begins the Ethiopian dialect known as Kenûs, which differs essentially from the dialects spoken farther to the S. by the Mahas and the Dongolah (comp. p. 304). Even in ancient Egypt, as we learn from a papyrus, the inhabitants of the Delta did not understand the speech of Elephantine.”1

“The scenery becomes tamer after the village of Kubânîyeh, on the W. bank. At el-‘Atârah, opposite, granite appears for the first time. Before we reach Assuân the scenery assumes entirely new aspects. As we approach the city, the scene presented to us is one of great and peculiar beauty. In front of us lies the S. extremity of the island of Elephantine (p. 271), with its houses shining from between the palm trees; the scarlet uniforms of British soldiers and their white tents, conspicuous at a considerable distance, form a strange feature in the landscape; and sandstone now gives place to masses of granite on the banks and in the channel of the stream. Farther towards the S. this rock forms the natural fortress known as the first cataract, which consists of innumerable cliffs of dark parti-coloured granite, among which the Nile pursues its rapid course towards Egypt by means of many narrow channels. 261/2 M. (58U M. from Cairo) Assuân.”2

“When the stream is low the steamers are compelled to anchor below Assuân, hut at other times they touch near the bazaar. Dhahabiyehs anchor at various points, sometimes beside the island of Elephantine opposite. — The mail-steamers remain here from Sun. or Wed. morning till Mon. or Thurs. afternoon at 3 p.m.; the three-weeks steamer halts 2 days (Sun. and Mon.) for a visit to Assuân and Philae; and the four-weeks steamer 2 1/2 days. Those who wish to proceed to Wâdi Halfah (p. 299) must quit the steamer on Mon. morning and take the train to Shellâl (Philae).— In 1890 a dhahabîyeh belonging to Messrs. Cook and Son, near the station, provided board and lodging for 1l. per day.”3

“Assuân, Coptic Suan (Arabic, with the article, Al-Suân, Assuân), the steamboat terminus for the lower Nile, with a post and telegraph office, lies on the E. bank, partly on the plain and partly on a hill, in N. lat. 24° 5′ 30″. The fertile strip here is narrow, but supports numerous date-palms, the fruit of which still enjoys a high reputation. The native inhabitants have increased under the British occupation to about 10,000; but that number is only a fraction of its former population, when according to Arabian authors, no less than 20,000 died of the plague at one time. Some of the houses are elegant, but the mosques do not repay a visit. The howling dervishes have a house here in which they meet on Fridays for prayer. A considerable trade is carried on in the products of the Sûdân and Abyssinia, brought hither on camels, and shipped northwards by the Nile to Kench, Assiut, or Cairo. Among the chief exports are ostrich feathers, ivory, india-rubber, senna, tamarinds, wax, skins, horns, and dried dates. The steamers and dhahabiyehs are here boarded by negroes, Nubians, and handsome Beduins, with artistically dressed curly hair, who offer for sale ostrich feathers and fans, silver rings and armlets, ivory hoops, weapons from Central Africa, small monkeys, amulets, beautiful basket-work, and aprons of leather fringe, the costume of the women of the Sudan, which they oddly call ‘Madama Nubia’. Grey and black ostrich feathers are comparatively cheap (8 piastres = 2 fr. each), larger and perfect white feathers cost 10-20 fr. apiece and upward. Travellers who desire to buy in quantity should betake themselves to one of the wholesale dealers in the town. The bazaar is like the bazaars of all Nile towns, but is distinguished for its excellent local pottery of great beauty of form. Candles, porter, ale, and even tolerable Dutch cigars may be obtained at a Turkish ‘bakkal’. — Copper money is, curiously enough, accepted very unwillingly in Assuân and the rest of Nubia; the traveller should provide himself beforehand with silver piastres.”4

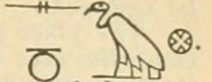

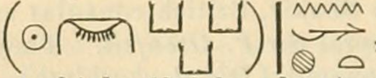

“HISTORY. The ancient Egyptian name of the town of Assuân was Sun (see fig. 1), that of the whole cataract-district was Senem (see fig. 2).”5

f

“The name Sun means ‘the place affording an opening or entrance’, because here the threshold of Egypt was crossed. The name seldom occurs in hieroglyphic inscriptions, because the metropolis or chief town of the nome to which Sun belonged, was Elephantine, on the island of that name. The place, however, is very ancient, for even under the 6th Dyn., the granite required by the builders of Lower Egypt was furnished by the quarries in its neighbourhood. In later times the city of the cataracts was frequently referred to by Greek and Roman writers under the name of Syene. It acquired special fame on account of its well (see below), and as the place of banishment of Juvenal in his old age.”6

“The Well of Syene, in which there was no shadow at midday, and which thus seemed to prove that Syene was situated under the tropic, has disappeared. The report of its existence led the learned Athenian Eratosthenes (276- 196 B.C.), attached to the Museum at Alexandria, to the discovery of the method of measuring the size of the earth that is still employed. ‘He selected the arc of the earth between Alexandria and Syene (Assuân) on the Nile, of which place he assumed that it was in the same meridian. Since he knew that the midday sun at the summer solstice cast no shadow within a radius of 300 stadia from Syene, and that in Alexandria at the same time the angle determined by the shadow of the sun-gnomon was equal to one-fiftieth of a circle, he correctly concluded that the distance between Alexandria and Syene must equal the fiftieth part of a meridian circle, or 7° 12′ [The actual difference between Alexandria (31° 12′) and Assuan (24° 5′ 30″) is only 7° 6’ 30″.]. The distance from Alexandria to Syene was taken by Eratosthenes simply at the popular estimate of 5300 stadia, equal to 593 M. (Lepsius) or 518 M. (Hultsch). Peschel. — A glance at the map shows that Assuân no longer lies under the tropic of Cancer, but somewhat to the N. of it, so that no shadowless well can exist there at present; but it has been calculated that in the 4th cent. B.C. Syene actually lay exactly under the tropic, whence we may gather that the Egyptians must have noticed the shadowless well long before Eratosthenes and must have known the true situation of the tropic.”7

“Juvenal was still living under Hadrian; but it is not quite certain whether, as is usually assumed, he was sent to Egypt by Domitian. The rhetorician and satirist, while living in Rome, had fiercely attacked the actor Paris, who was a court-favourite, and he was on that account removed from the capital. He was not exactly banished but appointed prefect of the garrison at Syene, on the most remote frontier of the empire. His trenchant muse found abundant material on the banks of the Nile. His 15th Satire describes the contest between the inhabitants of Ombos and Tentyra (Denderah) at a festival at Koptos. The two hostile nomes, whom he erroneously calls neighbours (‘vicinos”), had long cherished a mutual enmity on account of the gods they worshipped. At Tentyra the crocodile was persecuted, while it was held sacred at Tentyra for the sake of Sebek who was worshipped there. Thus arose a strife resembling that mentioned on p. 7. The Tentyritians even slew a man of Ombos and devoured him. Juvenal is indignant, and indicates that his residence on the Nile had by no means taught him to love the Egyptians. If he composed the 15th satire at Syene, that town has the honour of being the birth-place of the following fine verses: —

‘That nature gave the noble man a feeling heart’

‘She proves herself, by giving him tears!’

‘This is the noblest part of all human nature’.

The 16th Satire, in which Egypt is again mentioned, seems to be erroneously ascribed to Juvenal. Doubts also attach to the authenticity of a frequently quoted edict of the emperor Diocletian, ordering the Christian churches on the Nile as far as Syene lo be torn down and the temples to be restored.”8

“The place suffered greatly at the hands of the Blemmyes, but became the seat of a Christian bishop, and appears to have rapidly regained its prosperity under the Khalifs. Leo Africanus (14th cent.) saw here some towers of unusual height, which can only be regarded as the pylons of some large temple, as they were named Barba by the natives, a name easily traced from the Egyptian ꜥpa erpe’ i.e. the temple.”9

“After the close of the 12th cent. Assuân suffered still more severely from the incursions of plundering Arab tribes, finally put a stop to by a Turkish garrison stationed here by the sultan Selîm, after the conquest of Egypt in 1517. Many of the present inhabitants claim descent from these Turks.”10

“To the S. and N. of the landing-place, at which various craft are always lying, two edifices project into the river. One of these is a ruined Arabian fort, the other a ruined building, probably a bath, for which stones of earlier buildings have been used, and dating more probably from the Khalifs than from Roman times. The upper part of the town presents large clay walls with few windows towards the stream; the lower part is screened by palm-groves, through whose green foliage gleam the outlines of crags, heaps of rubbish, a dark gray clay wall, and a pure white minaret. Huge granite cliffs rise from the stream. To the W. lies the green and fertile island of Elephantine, shaped like the head of a lance, and still farther to the W., on the Libyan bank, rises a ruined Arab castle, projecting darkly from the yellow sand-slopes of the range of hills across which the telegraph-wires are conducted. To the E. the prospect is bounded by the Arabian hills, in which, more to the S., are some huge empty graves of saints. Everywhere the eye finds rest. The Nile, with its divided channel, appears small; but it still preserves its venerable aspect, for everywhere, even on the rocks by the stream, are inscriptions and numerous memorials of the grand old times, especially as we look towards the island.”11

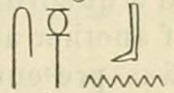

“In Antiquities, Assuân is not very rich. Besides the small Ptolemaic Temple beside the land-route to Philae (p. 274), only a few Rock Inscriptions on the river-bank call for mention [The remains of two other temples are described in the Description de I’Egypte, but both have now disappeared. One was a tetrastyle Portico, the other a Hall, dedicated by the emperor Nerva to the gods of Assûan, Khnum, Sati, Anuke, and Nephthys, and to Osiris, Isis, Sebek, and Hathor. Champollion saw the latter in 1829.]. One dates from Rameren of the 6th Dyn.; several from the 12th Dyn., from Usertesen I., from the 35th year of Amenemha II. coinciding with the 3rd year of his adopted successor Usertesen II., and one from the 5th year of the same king. In both the latter a certain Mentuhotep is mentioned. There is also a stele of the 10th year of Usertesen III. and one with the name Neferhotep, of the 13th Dynasty. Another important stele, dating from the first year of Tutmes II. (see fig. 3) contains a detailed report of the conquest of some rebellious S. tribes in the land of Kush and the district of Kenes. Some inscriptions of a certain Senmut before Hatasu and her daughter Raneferu record the quarrying and despatch of two large obelisks; another is from the 9th year of Seti I.; others are by a Mes (Moses) under Merenptah I.; and another is by a certain Seti, a royal son of Kush and president of the gold-land of Siptah, and his minister Bai.”12

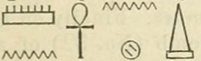

“In 1885-86 some important Tombs of the 6th and 12th Dyn. were opened on the hills (‘Mount Grenfell’) lying to the W. opposite Assuân, first by Mustafah Shakir, British consular agent at Assuân, and then by Major-general Sir F. Grenfell. They lie about 1/4 hr. to the N. of the W. convent (Dêr el-gharbîyeh). We cross the river in the small boat and land at a ruined stone quay, whence an ancient staircase, hewn in the rock, ascends for about 150 ft., flanked on either side by a wall of more recent date. The stairs are in three flights, from the top of each of which inclined planes lead towards the tombs, evidently intended for the transport of the sarcophagi. At the summit of the staircase is a platform with tombs of the 6th and 12th Dynasties [Described by Budge in the Proceedings of the Soc. for Bibl. Arch, for November 1887, and by Bouriant in the Recueil X, p. 181.]. Tomb No. 26, with a curious door placed one-third up the height of another door, belongs to a court-official named Saben (see fig. 4), who flourished under Neferkara Pepi II. (6th Dyn.) and was employed on the pyramid of that king Men-ankh (see fig. 5) (see Plan, Vol. I., p. 378).”13

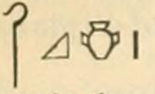

“The tomb consists of an oblong hall (69 ft. by 26 ft.), with a ceiling supported by 14 square pillars. Close to the entrance, beside the first pillar on the right, is the standing figure of Saben, with red complexion and black hair. On the back-wall the deceased appears spearing fish from a boat, with a companion engaged in catching birds that rise from a bed of papyrus-plants. To the left is a passage, leading to a winding mummy-shaft. On the left side of this tomb, and not separated from it by any partition wall, lies Tomb. No. 25, belonging to a certain Mekhu (see fig. 6) This contains eighteen columns in three rows, resembling the so-called proto-Doric columns in the tombs at Benihasan (p. 12). Between the first two rows stands a square stone, probably used as an altar. To the right of the entrance are a few paintings. Mekhu leans upon a staff, being perhaps lame, while offerings are presented to him (one of his sons was also named Mekhu, his wife Aba was a priestess of Hathor, while another son, called Saben, was possibly the owner of tomb 26). In the adjoining paintings Mekhu is shown making an offering himself and ploughing with oxen and reaping. Good representations of Egyptian donkeys. From the point where the two tombs touch, another passage leads to a mummy-shaft, at the back of which is a square chamber.

Climbing up to the right from this double tomb we find several other tombs, most of which have no inscriptions. One belongs to Heḳ-ab (see fig. 7), son of Apt and of Penatmai. A four-line inscription over the entrance mentions festivals of the dead. Another important tomb is No. 31, belonging to Ranubkaunekht (see fig. 8), who appears from his name to have been a high official under Amenemha I. It seems also to be the sepulchre of his son (?) Si Renput (son of Satihotep), whose portrait is of frequent occurrence in this tomb and who is named commander of the light troops in the S. frontier districts. Beyond a narrow passage follows a hall with 6 square columns, and then another passage with three recesses on each side, the first on the left containing a bearded figure of Osiris. At the end of the second passage is a small chamber with four columns, whence a long passage leads to the right to a quadruple shaft. Farther on, at the top of another ascent, is a tomb, named after the Prince of Naples who was present at its opening, and belonging to Baikhenu, a priest at the pyramid of Pepi II. (p. 269). Then the large sepulchres of Khunes and Semnes. Finally on the N. side of the same hill is the interesting tomb (No. 32) of another Si Renput (son of Tena), who served under Usertesen I., and was grandfather or great-grandfather of the above-named Si Renput through his daughter Satihotep. To the right and left of the entrance are some half-defaced inscriptions. The antechamber has seven pillars, on one of which (to the right) reference is made to a campaign undertaken by the king for the subjection of a hostile tribe (Kat?). Another important inscription (unfortunately damaged), over the entrance to the rock-tomb proper, treats of the influential position enjoyed by Si Renput under the king and in the campaign against Kush (Ethiopia). To the left scenes of fish-spearing and fowling, and cattle. In the interior are a small tetrastyle hall, a long passage, and then another tetrastyle hall, at the back of which is a recess. Wo may descend direct from this tomb to the bank of river.”14

“Among the other points to be visited hence are Elephantine, the small Temple of the Ptolemies, the old Cemeteries, and the Quarries on the way In Philae.”15

- Baedeker 1892, 265. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 265-66. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 266. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 266. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 267. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 267. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 267. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 267-8. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 268. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 268. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 268. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 268-9. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 269. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 269-70. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 270. ↩