Written by Fabio Calo

Biography

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus was a Roman poet of the 1st century CE. Born on the 3rd of November 39 CE in Corduba (Córdoba) in the Hispania Baetica, he stemmed from one of the most eminent and influential families of the region: He was the grandson of the elder, and the nephew of the younger Seneca.1 The latter took him into his care in Rome in his early childhood and it is probably much due to his affiliation to the philosopher that the emperor Nero called him into his circle of literate associates.2 By the year 65 CE, however, the young poet and the young emperor had fallen out and Lucan found himself taking part in the ‘Pisonian conspiracy’, a failed plot to assassinate Nero.3 Lucan was arrested and forced to commit suicide on the 30th of April 65 CE.4

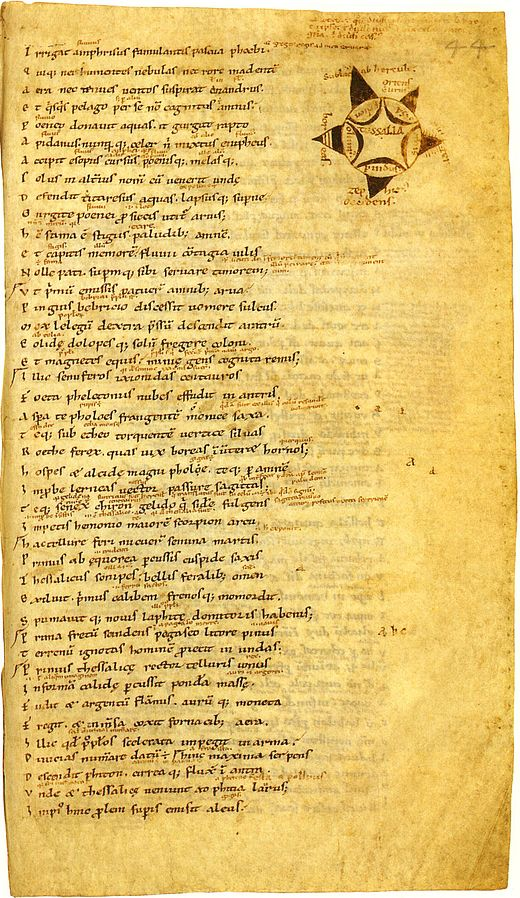

Lucan devoted most of his literary activity to the composition of epics.5 His only surviving, and at the same time major poetical work is the Pharsalia, or bellum civile. It treats in verse the civil war between Caesar and the senatorial aristocracy, rallied behind the banner of the illustrious commander Pompeius Magnus. It is in this work where we not only find passages on Egypt,6 but also scattered references to Syene.

References to Syene

The first mentioning of Syene picks up a geographical feature of that city, the absence of shadows:

“calida medius mihi cognitus axis Aegypto atque umbras nusquam flectente Syene;”

“[…] the torrid zone is known to me in sultry Egypt and Syene where the shadows fall perpendicular;”7

This information is, as Hardie notes, incorrect. Only once a year would the sun fall exactly vertically on Syene, at midsummer noon.8 This had been noticed already by Macrobius, who in his commentary to Cicero writes:

“et eo die quo sol certam partem ingreditur Cancri, hora diei sexta, quoniam sol tunc super ipsum invenitur verticem civitatis, nulla illic potest in terram de quolibet corpore umbra iactari sed nec stilus hemisphaerii monstrantis horas, quem gnomona vocant, tunc de se potest umbram creare. Et hoc est quod Lucanus dicere voluit, nec tamen plene ut habetur absolvit. Dicendo enim ‘atque umbras numquam flectente Syene’ rem quidem attigit, sed turbavit verum. Non enim numquam flectit, sed uno tempore, quod cum sua ratione rettulimus.”

“At noon of the day when the sun reaches Cancer, as it is directly over that city, there can be no shadow cast upon the earth by any object, not even by the stylus or gnomon of a sundial, which marks the passage of the hours on the dial. This is what the poet Lucan meant to express though his actual statement is inadequate; for the words ‘Syene never casting shadows’ allude to the phenomenon but confound the truth. To say that it never casts shadows is incorrect; the only time it does not has been reported and explained above.”9

Of course, this phenomenon had already been described by the geographer Strabo ca. 24 BCE10 and would later be reiterated by Ammianus Marcellinus ca. 391 CE.11 Where Lucan got his information from is unclear. Among his sources were certainly the Naturales quaestiones of his uncle Seneca, as well as a (now lost) treatise De situ et sacris Aegyptiorum and other geographical works.12 Ehlers notes with regard to Lucan’s description of the course of the Nile, that the poet values poetical considerations higher than geographical accuracy.13 Recently, Meyer has shown that Lucan employs repetitions and exaggerations of natural phenomena for the sake of symbolism.14 With regard to the position of the sun, she explains that it serves to emphasize the heat exposure of a given region.15 As Meyer shows, Lucan has applied climatic features of the equator to the region along the tropic of cancer (calida medius […] axis Aegypto atque […] Syene)16. This, so she explains, opens the locations along this tropic to a whole range of symbolic interpretations. By portraying places under the tropic as lying directly under the sun, Lucan emphasizes their character as boundaries to a more hostile climatic region – or even places them already inside it.17 This reinforces the point with which Pompey is rallying his soldiers behind his leadership in the impending civil war with Caesar: that no part of the (habitable) world was left untouched by the senior general; that “the whole earth, beneath whatever clime it lies, is occupied by [his] trophies.”18

There is also the recurring motif of the ‘stoic ekpyrosis’, the all-consuming fire at the end of the universe’s life cycle. Since the described heat and drought of the region around the northern tropic are linked with the ekpyrosis elsewhere,19 by applying equatorial sun exposure to Syene, Lucan could have also intended to evoke and amplify that association. In that sense, the scientifically inaccurate treatment of Syene could serve several kinds of poetical purposes.

Apart from this, there is not much else that Lucan writes about Syene. In addition to passing references when describing the heat and drought of the region,20 Lucan describes Philae as dividing Egypt from Arabia (“dirimunt Arabum populis Aegyptia rura”)21 and being a claustrum of the Egyptian kingdom (“regni claustra Philae”).22 This can be a ‘gateway’ or ‘key’ through which to control access to a region, or a ‘barrier’, specifically a ‘natural barrier’ or ‘boundary’23 – or even, in a military sense, a ‘fortress’ or ‘defence’.24 What else he might have had to write about Syene and the First Cataract region, we don’t know. The tenth book of the Pharsalia ends abruptly, most likely broken off by his forced suicide in 65 CE.25

- His father M. Annaeus Mela was the youngest son of the elder Seneca and the brother of the philosopher Seneca. Their ancestors are commonly thought to have been Italian colonists who had settled on the Iberian Peninsula. His mother Acilia was the daughter of the rhetorician Acilius Lucanus, also from Corduba. Thus, Lucan inherited his cognomen from his maternal grandfather. For the biographical information about Lucan see Marx 1894; Elvers, Vessey 1999. ↩

- See Tac. Ann. XV 49; Cass. Dio LXII 29,4; Suet. Vita Luc.; Marx 1894, 2227. ↩

- See Tac. Ann. XV 49. The most extensive account of this plot is given in Tac. Ann. XV 48-74; see also Cass. Dio LXII 24-7; Suet. Nero 36,1-2. It is told that Lucan had invoked the envy of the emperor by surpassing him in talent: see Tac. ann. XV 49 (vanus adsimulatione); Cass. Dio LXII 29. While this is of course possible, it may very well have been a reaction to the staunchly pro-‘republican’ theme of his Pharsalia – or it may just have been a by-product of Nero’s estrangement from Seneca: see Marx 1894, 2229; Elvers, Vessey 1999, 455. ↩

- Reports that Lucan, in a desperate attempt to save his own skin, tried to involve his own mother Acilia in the plot (see Suet. Vita Luc.; Tac. Ann. XV 56,3) are perhaps just parts of political vituperation against his family: see Elvers, Vessey 1999, 455. ↩

- One innovative aspect of his way of epical narration is the absence of godly intervention, see Marx 1894, 2230; Elvers, Vessey 1999, 455. ↩

- The country recieves a harsh verdict, as it was, in his mind, guilty of bringing an unworthy end to a Roman citizen (noxia civili tellus Aegyptia fato) – to Pompey: see Luc. VIII 823-34. This is Ehler’s interpretation (“Du mit Mordschuld an einem Bürger Roms beladenes Ägypterland”), which seems to me more convincing than Duffs interpretation of Egypt as facilitator of the civil war’s outcome. Vessey seems to blend both interpretations together: “das in L.’ Augen für den Verrat und Mord an Pompeius und daher für die Auslöschung der libertas zu verfluchen ist” (Elvers, Vessey 1999, 456, italics in the original). ↩

- Luc. II 586-7 (transl. J. D. Duff). ↩

- See Hardie 1890, 13. ↩

- Macrob. In Somn. II 7,15-6 (transl. W. H. Stahl). Note that Macrobius cites Lucan with numquam rather than with nusquam, as the Loeb edition of Lucan does. It may be that Lucan wanted to say that the sun sheds shadows in Syene nusquam – nowhere – and that Marcobius misread him to mean that the sun shed shadows numquam – never: see the commentary by Heberlein in his edition of Macrobius (p. 446 n. 88). Interestingly enough, this also appears to have happened to Hardie 1890, 13: he cites Lucan with nunquam, mostly leaning on the English edition by Haskins, which in fact reads nusquam. In his commentary to verse 587, Haskins ‘explains’ that Syene was lying exactly under the equator. This is, of course, incorrect: Syene lies (roughly) under the northern tropic (see also Hardie 1890, 13). Whether Haskins was merely explaining the statement of Lucan and thought a correction unnecessary, or whether he himself did not notice the error, is unclear to me. In any event, to solve this puzzle is not at the centre of the argument. Lucan clearly does not confine the phenomenon he mentions to the midsummer noon, nor to any specific frame of time. Macrobius and Hardie are in their right to point that out. ↩

- See Str. XVII 1,48. ↩

- See Amm. XXII 15,31. ↩

- See Ehlers (ed.) 1978, 560. ↩

- See Ehlers (ed.) 1978, 560-1. ↩

- See Meyer 2023, 229-30. ↩

- See Meyer 2023, 142. That is the Siwa Oasis in the Lybian desert. ↩

- Luc. II 586-7. ↩

- See Meyer 2023, 141. This is the torrid zone of the five-zone model. ↩

- Luc. 2,583–584 (transl. Duff): Pars mundi mihi nulla vacat; sed tota tenetur / Terra meis, quocumque iacet sub sole, tropaeis. ↩

- See Meyer 2023, 241-2. ↩

- See Luc. VIII 851-2; X 234-5. ↩

- Luc. X 312. ↩

- Luc. X 313. ↩

- See Oxford Latin Dictionary (ed. Glare), 335. ↩

- See A Latin Dictionary (ed. Lewis, Short), 351, which cites the line as an example for that use. ↩

- See Marx 1894, 2232. ↩