Written by Julia Schulz

Biography

Otto Friedrich von Richter (see fig. 1) was born on August 6, 1791, in Vastse-Kuuste, Estonia. Richter studied in Heidelberg, Vienna, and Constantinople where he met renown scholars such as Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall1, Friedrich Schlegel2 and Count Wenzel (II.) Rzewuski3. Richter also seems to have had contact with Wilhelm von Humboldt.4

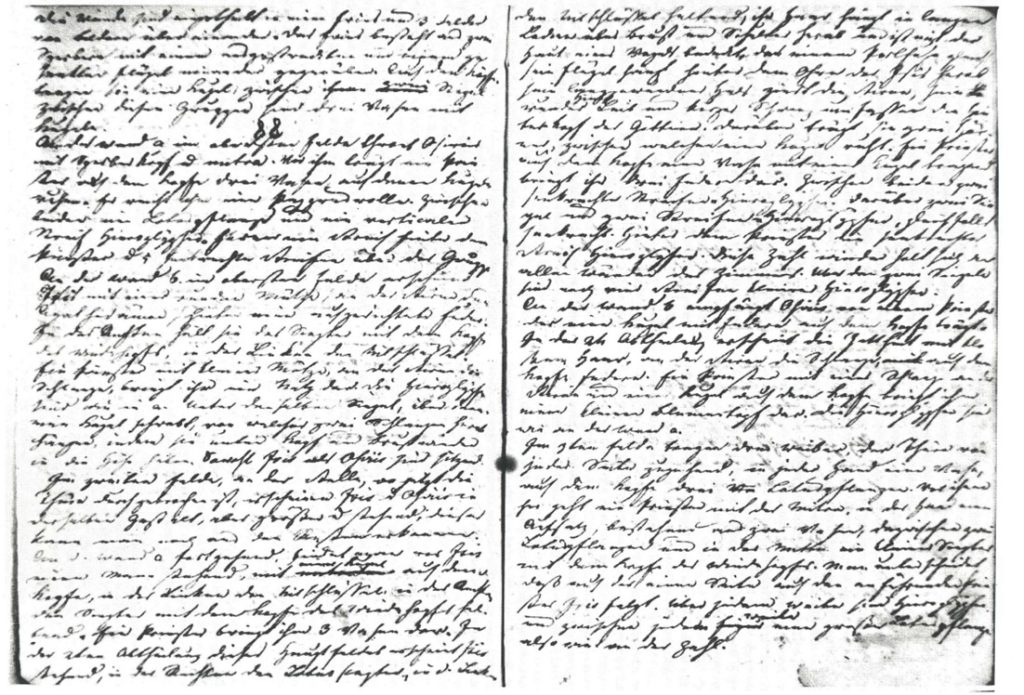

Richter was a philologist and traveler and one of the first who not only visited Egypt, but also envisaged a journey into Nubia.5 After traveling through the Levant Richter and his friend Sven Fredik Lidman6, together with their Armenian servant Kirkor set off for Alexandria onboard of a Greek ship on March 30th, 1815. Their journey through Egypt is being reported in his letters to his mother and in his diary entries (see fig. 2).7 However, his scientific observations were never properly published because of his unexpected death by dysentery or cholera on his way back from Egypt via Smyrna on August 13th, 1816. A selection of Richter’s notes and sketches was printed posthumously in 1822 by his former teacher Gustav Ewers under the title “Wallfahrten im Morgenlande”.8 However, the parts on Egypt and Nubia were first left out and only later published by Friedrich Hinkel under the title “Zwei baltendeutsche Reisende in Ägypten und Nubien, 1815 und 1823“ in 2002.9 Also recently, another version of Richter’s diary, copied by an unknown author, has been found and published in parts by Sergei Stadnikov in 2000.10

Richter’s account of the First Cataract region

Richter and his party arrived in Aswan on May 30th, 1815, and he mentions in his letter to his mother how the Nile was so shallow that he at one point could just walk to Elephantine:

„Am 30sten kamen wir endlich in Assuan an. Hier ist der Nil still und spiegelklar; Dörfer und grüne Wälder, schwarze Felsen, gekrönt mit Trümmern aller Zeiten und Völker, spiegeln sich – selbst des Nachts beim Sternenlicht – in seinem tiefen Blau; eine Sandwüste, citronengelb, zieht einen weiten Kreis umher, an dem sich wiederum schwarze Berge mit wilden Zacken erheben. Nie habe ich eine seltsamere Gegend gesehen. Der Nil war an einer Stelle so seicht, daß ich bequem durchwatete um nach Elephantine zu gehen.“11

On the next day they left their boat at Aswan and rode on horses accompanied by one of the commanders, named Hussein Kaschef, on his dromedary through the desert to Philae. In his letters, Richter reports that they visited the buildings of the island of Philae, rented a new boat for their travels into Nubia and passed the famous cataracts on their way back:

„[…] nach Philae, wo wir die schönen Gebäude dieser zauberischen Insel betrachteten. Auf dem Rückwege kam ich an die berühmten Cataracten vorbei; die aber kaum zu sehen waren. Wir ließen unser Boot in Essuan und mietheten ein Andres zur Reise nach Nubien.“12

Richter’s journey into Lower Nubia

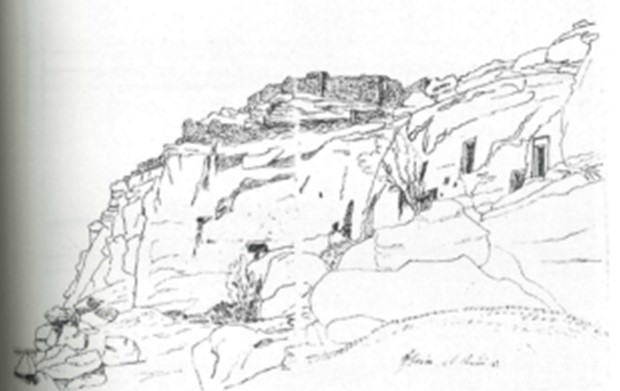

On 1st of June they continued their journey south Richter describes how they passed by the antique sites of Debod, Dehmit, Qertassi, Taffe, Kalabsche, Dendur, Dakka, Kubban and Korosko all of which they planned to inspect further on their way back. They managed to sail as far as Derr before conflicts between local ruler further south made them interrupt their journey and ultimately turn back.13

.

.

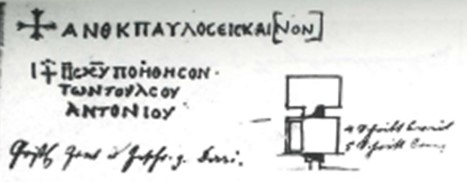

All in all, Richter studied 24 Nubian sites, complementing his entries with a series of sketches, depicting the course of the Nile, passing landmarks, and the antique structures located at the above mentioned sites.14 He also recorded a Greek Inscription (see fig. 5) found in a rock tomb at Derr which was built in Ptolemaic times and later reused by Christians.

They spent nearly three weeks south of the First Cataract until they returned to Aswan on June 20th:

„Am 20sten waren wir wieder in Philae. Aber hier ward unsre Reise nur ein Abschiednehmen von aller Schönheiten dieses Wunderlandes, mit dem Gedanken, sie wohl nie wiederzusehen.“15

The legacy of his purchases

Richter bought several antiques during his visit in Egypt which he recalls in a letter to his mother in June 1815.16 Most of his belongings, including the artefacts he acquired while traveling, were brought back to his hometown in Estonia and given to his father who entrusted the overall 126 antiques, books, coins and manuscripts to the art museum and library of the University of Tartu in 1819.17 A catalog of his purchases was published in the “Wallfahrten im Morgenlande”.18 Those artefacts include an anthropomorph wooden coffin, two human mummies, several animal mummies, uschebtis, scarabs, bronze figures depicting priests and various Greek coins.19 A large part of the collection was relocated during World War I and has yet to be returned.20

- A German orientalist of the early 19th century (Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 4). ↩

- A German author, linguist, and theorist of pre romanticism (Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 5). ↩

- A Polish orientalist who was initiator and sponsor of the oriental paper “Fundgruben des Orients”, published between 1809-1818 (Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 5). ↩

- Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 2; 4-6. ↩

- Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 1. They managed to travel as far as Qasr Ibrim before they had to head back north because of the difficult political and potentially dangerous situation in the region (Von Richter 1822, VII; Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 8). ↩

- A Swedish priest (Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 6). ↩

- Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 2; 7. ↩

- Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 8-9. Richter, O. F. von; Ewers, J. P. G. (ed.), „Wallfahrten im Morgenlande“ (Berlin 1822). Online available. ↩

- The authors voice their opinion that this might be either due to the sheer capacity of the Egyptian-Nubian report or the more scientific character used in this part which would not have been as appealing to a wider readership at the time of publication (Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 9). ↩

- Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 9-10. A complete list of Stadnikov’s publications about Otto Friedrich von Richter can be found in the Sources for this article. ↩

- Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 24. ↩

- Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 24. ↩

- Hinkel 2002, vii. ↩

- Hinkel 2002, vii. Richter’s intention for cataloging the archaeological sites was to compare the Nubian temples with the most significant Persian and Indian structures (Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 8). ↩

- Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 24-25; 27. ↩

- Jürjo, Stadnikov 2008, 17-31. ↩

- Stadnikov 1991, 200; Hinkel 2002, viii-ix. ↩

- Online available. ↩

- von Richter 1822, 614-25. ↩

- Hinkel 2002, ix. ↩