Written by Julius Jürgens

Biography

Richard Pococke (1704-1765)1 was a British clergyman and traveller. He visited North Africa and the Near East in the 18th century, primarily to explore the remains of ancient Egyptian architecture. In the 1730s he went to the Upper Egyptian city of Aswan, which at the time of his visit was under control of the Ottoman Empire. His travel experiences were published in 1743 in the first volume of “A description of the East and some other countries“2, a kind of itinerary including descriptions of various ancient sites in and around Aswan, as well as the author’s intercultural contacts with the local population.

Travel Report

First of all, Pococke differs between the “modern” city of Aswan and the ancient town of Syene, whose hose ruins he described as being located between two hills south of then-modern Aswan.3 There, he saw extensive areas “full of ruins of unburnt brick”4, which he interpreted as the remains of medieval Aswan. Furthermore, he discovered various ancient ruins, such as the so-called Observatory5 lying “between the river and the brow of the hill to the east”6 and build over a well, which was used for astronomical observations, according to Strabo.7 He gave an exact drawing of this building which is depicted here as Fig. 2.

Fig. 3: Stone-quarry by Aswan, Photo by Stefanie Schmidt.

During his stay, Pococke also visited the famous ancient quarries east of the city (fig. 3), where the distinctive red granite was mined in antiquity. At that place, he observed various remains of unfinished stone work, particularly a big square column that was only partly worked out.8 This is certainly the so called unfinished obelisk of Aswan, which can still be seen to this day. Based on the mining marks, he tried to understand how the ancient stonecutters had worked: “I saw some columns marked out in the quarries, and shaped on two sides[…]; they seem to have worked in round the stones with a narrow tool, and when the stones were almost separated, […] they forced them out of their beds with large wedges”.9

On the island of Elephantine he saw the ruins of an ancient settlement, of the Temple of Khnum, and the Nilometer.10 A wall in front of the temple bore a Greek inscription ‒ supposedly from the time of Diocletian.11 Furthermore, he noticed that the ground was raised on the island’s south end, “probably by the rubbish of a town of the middle ages”.12 The once independent town of Elephantine had shrunk to a small and sparsely populated settlement.

After crossing a sandy valley at the Nile’s west bank, Pococke found a deserted monastery with Christian paintings and Coptic inscriptions in it.13 As he saw a painting of what he thought was the portrait of St. George, he supposed it was dedicated to this saint. These ruins are that of Dayr Anba Hadra, also known as the monastery of St. Simeon.

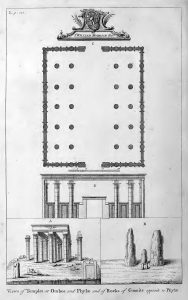

Fig. 4: Views of Temples

On the island of Philae, Pococke explored the ruins of the surrounding fortification and the temple complex, which is shown in Fig. 4.14 He assumed that the island was an immensely sacred place, as Osiris himself was thought to be buried there and thus, it must have been inhabited by priests only.15

In a short section of his report, Pococke also discussed the course of the border of ancient Egypt, which he suspected to be in the area around Aswan.16 He came to the conclusion, that Elephantine was the western border between Egypt and Ethiopia in this particular area, while the southern border must have been near Qasr Ibrim.17

The last stop of his visit in Aswan was the first cataract and a port upstream on the Nile, where he found “no village, only some little hutts [sic] made of mats and reeds.”18 As he reports, boats from “Ethiopia”, which might have been his term for all places south of Egypt, arrived here to unload and transport their goods via land to Aswan, from where northbound shipping was possible.19 This procedure was already used in ancient times as this part of the Nile was unnavigable due to the rocky cataract. As one good of import Pococke identified dates, which were both consumed by Aswan’s population as well as being traded to Lower Egypt.20

- https://catalogues.royalsociety.org/CalmView/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Persons&id=NA8009 (14.02.2021). ↩

- https://archive.org/details/gri_33125009339603/page/n225/mode/2up p. 116-123 (22.03.2021) ↩

- Pococke 1743, 116. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 116. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 117. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 117. ↩

- Str. XVII 1.48. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 117. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 117. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 117‒118. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 118; 278 (= Prose sur pierre 65 = Th.Sy. 252), Brennan 1989, 193-205 (= IGRR 1.1291 = SB 5.8393). ↩

- Pococke 1743, 118. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 118. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 120-121. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 120. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 118 and Str. XVII 1.48. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 118. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 121. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 121‒122. ↩

- Pococke 1743, 121. ↩