Both the tourist-steamers and the mail-steamers allow one day for a visit to Philae. Tourists by the four-weeks steamer may visit the island twice, and they are recommended to do so. Travellers to Nubia who are unable to find time to visit Philae on the outward journey, should not fail to devote to it at least a few hours on the return, either on the evening of reaching Shellâl, or on the next morning, after spending the night on board the steamer. When more than one visit is paid the traveller should come once by rail, once by land returning by boat. Accommodation at Philae can only be obtained if a dhahabîyeh happens to be there.1

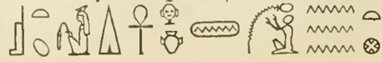

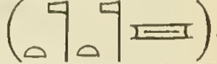

The name of Philae is derived from the old Egyptian, in which it is called, with the article, Pa-alek (see fig. 1), or usually merely Alek (see fig. 2). This name occurs thousands of times on the island itself, with many variations, and probably means the island of Lek, i.e. of Ceasing or of the End2, referring to the Nile-voyage hither from the N. The Copts called it Pilak or Pelak, and the Arabs used to call it Bilak. Now-a-days none of these names are known to the natives, who usually call the island Anas el-Wogûd, after the hero of one of the tales in the Thousand and One Nights, which has undergone considerable change in the Egyptian version and has its scene transferred to Philae.3

The boatmen relate it as follows. ‘Once upon a time there was a king, who had a handsome favourite named Anas el-Wogûd, and a vizier, whose daughter was named Zahr el-Ward, i.e. Flower of the Rose. The two young people saw and fell in love with each other, and found opportunities of meeting secretly, until they were discovered through the imprudence of the maiden’s attendant. The vizier was violently enraged and, in order to secure his daughter from the farther pursuit of the young man, despatched her to the island of Philae, where he caused her to be imprisoned in a strong castle (the temple of Isis) and closely guarded. But Anas el-Wogûd could not forget his love. He forsook the court and wandered far and wide in search of her, and in the course of his travels showed kindness to various animals in the desert and elsewhere. At last a hermit told him that he would find Zahr el-Ward on the island of Philae. He arrived on the bank of the river and beheld the walls of the castle, but was unable to reach the island, for the water all around it was alive with crocodiles. As he stood lamenting his fate one of the dangerous monsters offered to convey him to the island on his back, out of gratitude for the young man’s previous kindness to animals. The lover was thus able to reach the prison of his mistress, and the guards suffered him to remain on the island, as he represented himself to be a persecuted merchant from a distant land. Birds belonging to Zahr el-Ward assured him that she was on the island, but he could never obtain sight of her. Meanwhile the lady also became unable longer to endure her fate. Letting herself down from her prison-window by means of a rope made of her clothes, she found a compassionate ship-master, who conveyed her from the island in which the lover she sought then was. Then followed another period of search and finally the meeting of the lovers. A marriage, with the consent of the father, ends the tale. — The Osiris Room on Philae (p. 295) is regarded by the Arabs as the bridal-chamber. The tale in the Arabian Nights ends as follows: ‘So they lived in the bosom of happiness to the advanced age, in which the roses of enjoyment shed their leaves and tender friendship must take the place of passion’.4

It seems as though this legend had arisen on Egypt soil, and as though it contained some echoes of the ancient mythology of Philae, e.g. the search of Isis for her beloved Osiris and the disposal of the goddess on an island in the Nile. It is even more remarkable that Anas el-Wogûd reached the island on a crocodile and that on the W. side of the temple of Isis is a relief (p. 294) representing the mummy of Osiris borne by a crocodile.5

The rocky island of Bigeh, opposite Philae, seems to have been an even earlier pilgrim-resort than the latter; yet there was probably a temple also on Philae in comparatively early times. In the 4th cent. B.C. this must have been either unimportant or in ruins, for the name of Nectanebus II. (see fig. 3), is the oldest name occurring as that of a builder, and that prince reigned as a rival king to the Persian Achaemenides and recognized only by his countrymen, at the date mentioned. The work that he began was zealously continued by the Ptolemies, who had greater resources at command, but even they left ample room for additional buildings and farther decorations at the hands of the Roman emperors down to Diocletian.6

The principal temple, like the island itself (see fig. 4), was sacred to Isis, whose priests resided here down to comparatively late times as a learned college. As one of the graves of Osiris was situated here, it early became a pilgrimage resort for the Egyptians, one of whose solemn oaths also was by the Osiris of Philae. When the cult of Isis as well as that of Serapis became known to the Hellenes and afterwards to the Romans, many Greek and Italian pilgrims flocked to the shrine of the mysterious, benign, and healing goddess. Even under Ptolemy Physkon the priests were compelled to petition the king to check the superabundant stream of pilgrims, who consumed the temple-stores and threatened to reduce the priests to the necessity of withholding from the gods their bounden offerings (comp. p. 284). On all the walls and columns of the temple are inscriptions, placed there by Greek or Roman officials, tourists, and pilgrims. They are most numerous in the S. part of the temple and in the oldest part, dating from Nectanebus. We know also that the goddess of Philae was worshipped by the Blemmyes (p. 302), who maintained the custom of human sacrifices until the time of Justinian. After Diocletian, who personally visited the island, had conquered these restless children of the desert, he destroyed the fortifications of Philae, and new temples were erected in which priests of the Blemmyes and Nobades were permitted to offer sacrifices to Isis along with the Egyptian priests. And these tribes even obtained the right of removing the miraculous image of the mighty goddess from the island at certain solemn festivals and of retaining it for some time. Even after all Egypt had long been christianized and the Thebaid was crowded with monks, the ancient pagan-worship still held sway in Nubia, in spite of the Edicts of Theodosius. The Nobades were converted to Christianity about 540 A.D. under the auspices of the Empress Theodora, and shortly afterwards Narses, sent by Justinian to Egypt, closed the temple of Isis on Philae, and sent its sacred contents to Constantinople. At first the people of Philae adopted the orthodox creed, but when Egypt was conquered by Islam, they exchanged this for the monophysite heresy. Although an inscription has been found in the pronaos in praise of a Bishop Theodorus (577 A.D.), who dedicated a portion at least of the temple of Isis to St. Stephen, it is doubtful whether Philae was ever an episcopal seat. It is certain, however, that Christian services were held in the hypostyle. The inscriptions and reliefs were plastered over with Nile-mud or had crosses carved upon them, so as to spare the feelings of the faithful and to exorcise the evil spirits. — Like Christianity, Islam was late in finding its way to Philae, and there is not a trace of a mosque or anything of that nature on the entire island. Nubia was effectually conquered in the 13th cent. by the Egyptian sultans, who included the cataract-region in their private domains, and thus secured the temples from destruction. — Philae was described in 1737 by Norden and Pococke, though at that time the natives were as hostile to strangers as they are now friendly and obliging.7

Isis, the chief deity of the island, is usually represented in the triad completed by Osiris and Horus, but she frequently also appears alone. Everywhere, in her various forms, she occupies the foremost place, just as Hathor does at Denderah. The deities of Philae include Ra and Month, the twin-gods Shu and Tefnut, Seb and Nut, Osiris-Unnofer (Agathodaemon) and Isis, Khnum and Sati, the gods of the cataracts, Horus the son of Isis, Hathor, and the child Horus. Thoth, Safekh, and other deities also frequently appear.8

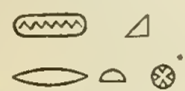

Philae is the pearl of Egypt, and those who have several days to spend at the cataract, should certainly take up their abode upon it. It is 420 yds. long, 150 yds. wide at the broadest part, and has a circumference of 980 yds. It is uninhabited, but an old watchman, who lives with his children and grandchildren on Bigeh, willingly assists travellers. The view of Philae from the river-bank is unexpectedly beautiful, especially to those who have just quitted the rugged rocks of the cataract or the arid desert; while, on the other hand, the views from the island, especially from its rocky S. end, are imposing and sometimes peculiarly wild.9

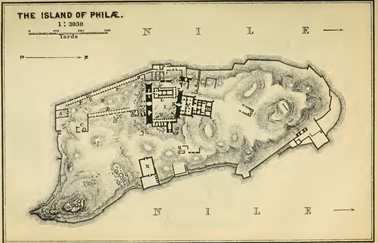

The buildings on the island which demand a visit are: 1. The *Temple of Isis (see fig. 5); 2. The Chapel of Hathor; 3. The Ruins and the Portal of Diocletian, in the N.W.; and 4. The *Kiosque. — Bigeh and the Cataract Islands also repay a visit.10

The Temple of Isis.

This beautiful structure dates from various periods, and its different parts show an almost capricious irregularity in their positions with reference to each other. The traveller is recommended to visit the various portions in the following order, but he is warned against lingering too long over any of them, if his time be limited or if his inspection have no special scientific aim. It is better to obtain a good general impression from the whole, than to examine the details minutely. In order to understand the arrangement of the temple, it must not be forgotten that it was preeminently a pilgrim-resort. The processions of pilgrims, whether they approached from Egypt or from Nubia, were compelled to steer for the S. end of the island, for the rocks to the N. of it prevented anything like a ceremonial approach. The portals of the temple therefore faced the S., and the festal boats disembarked their passengers on the S. coast. We likewise begin our visit from the S., or more exactly from the extreme S.W., to which we proceed direct from the landing-place. Our attention is first attracted by the strong erection of hewn stones facing the stream. The steps of a Stone Staircase within the quay-wall are still to be seen on the S.W. coast; and there was another staircase on the S. coast, to the E. of the building of Nectanebus.11

a. The Building of Nectanebus (Pl. A). Two Obelisks flanked the entrance to the hypaethral Force-Court, which the pilgrim entered first, and where he was received, and perhaps also examined and taxed. With the exception of the central portion of the first pylon (p. 287), dating from this same king, Nectanebus II., this is the oldest part of the whole temple. The obelisks, made of sandstone, instead of the usual granite, were small and stood upon stone chests. The W. obelisk is still standing, but the E. obelisk is represented by its chest merely.12

The E. obelisk itself was found prostrate by Bankes in 1815, and at his request removed to Alexandria by Belzoni, despite the protests of Drovetti who regarded it as his private property. From Alexandria it was taken to England, where it now stands at Kingston Hall in Dorsetshire. On the lowest part of the pedestal is a long Greek inscription containing a petition addressed by the priests of Isis to King Euergetes II. and his two wives, against the expense caused by the too frequent visits of royal officials and their retinues, which impoverished the temple. Above this are two other inscriptions, only fragments of which are preserved, in which the granting of the petition by the king and the con- sequent royal decree are announced.13

This obelisk has been of the greatest importance for the interpretation of the Egyptian hieroglyphics. The names of Ptolemy Euergetes and Cleopatra, which occur in Greek on the pedestal, were discovered by Champollion in 1822 on the obelisk itself, and from the latter name he was enabled to add a few more alphabetical signs to those already ascertained from the Rosetta decree (Vol. I., p. 111).14

The W. Obelisk, as we have said, remains in situ though it has lost its point. Upon it is inscribed, in Greek, a petition from Theodotos, son of Agesiphon, to Isis and her fellow-gods, dating from the time of Neos Dionysus. There are also some Arabic inscriptions.15

The hypaethral vestibule was bounded on each side (E. and W.) by six columns and one of the obelisks. The six W. columns are still standing, but only three stumps of the E. row remain. Between the columns were screen-walls, half as high as the shafts, and adorned with concave cornices and balustrades of Uraeus-serpents. The columns, only 2 1/6 ft. in thickness, are 15 1/3 ft. high, and have calyx-capitals supporting an abacus decorated with the Hathormask, on which rests a small chapel. These capitals, which resemble those of the Ptolemaic epoch, are specially remarkable, as they were erected by Nectanebus before the period of the Lagidae. Nectanebus who maintained himself for some time in opposition to the Persian kings, appears to have delighted in comparing himself to the ancient Pharaohs, as we may gather from his first name Ra-kheper-ka, which was also that of Usertesen I. of the 12th Dyn.; and it is possible that he adopted, in the same spirit, old and forgotten artistic forms in his erections. It is certain that the Hathormask at the top of the columns is only found earlier than his time on the monuments of the 18th Dyn. at Dêr el-baḥri (p. 223) and el-Kâb (p. 236). The architects of the Ptolemies were afterwards attracted by the abacus adorned with the countenance of the goddess of Denderah, adopted it, and farther developed the sculptured calyx-capital, here first introduced by Nectanebus. — On the W. and E. sides of each of the six standing columns are dedication-inscriptions. On the outer (W.) side of the most southerly column (next to the obelisk) is the inscription: ‘The good god, lord of both worlds, Ra-kheper-ka, son of the sun and lord of the diadems, Nectanebus, the ever-living, erected this sumptuous building for his mother Isis, the bestower of life, in order to enlarge her dwelling with excellent work, for time and for eternity’. — On the outer side of the third column the name of Philae appears as Alek (see fig. 6) (with the article, P-alek), a form found at many other places, and the mistress of the island is named as Isis (see fig. 7), the life giving goddess of Aab., i.e. of Abaton or the holy island. The last name deserves mention here, for the spot known to the ancients as Abaton, which must have been peculiarly holy in their eyes, is named innumerable times in the inscriptions of the temple of lsis. It must therefore be looked for on Philae itself. The inscription on the Architrave of the outer or West Side states that the king erected this building for his mother Isis, and that he rebuilt the hall lor her of good white hewn stone, surrounded with columns, with inscriptions throughout its whole extent, and, as the line below the architrave adds, painted in colours. The inner side of the architrave bears an invocation to Isis, mother of the gods.16

This little temple had doors on the E. and W. sides, not, however, opposite to each other, and another on the N. side, next the main temple. The last leads into a spacious Fore-Court (PI. B), enclosed on the right and loft by covered Colonnades. The W. colonnade (PI. F) follows the bank of the river, while that to the E. or right (PI. D) runs in the direction of the centre [sic.] of the first great pylon, but not at right angles to it, affording an example of the variety of axial direction exhibited throughout the temple.17

When we remember that a portion of the first pylon and the hypaethral space, which we have just quitted, were built by Nectanebus, and that all the other parts of the temple are of later data, we have an adequate explanation of the great irregularity displayed in its plan. It is quite certain that the structures that now bear the name of Nectanebus (a portal and a vestibule) were not the only buildings on Philae; under that king, for the construction of every temple, without exception, began with the sanctuary and ended with the doors. We may assume that an extensive temple stood here before its removal by the Persians; and that the latter largely destroyed the works of their rival. The parts that were spared were then incorporated by the Ptolemaic builders, while the Romans united the work of the Lagidae with the ancient vestibule of Nectanebus by means of the tapering peristyle court.18

b. The Colonnaded Court. This space is bounded on the W. side by a long wall, pierced here and there with windows, which, based on a firm substructure on the river-bank, forms the back of a narrow, but unusually long Colonnade (PI. F; 100 yds.). The latter, built under the Romans, has a row of 31 (formerly 32) columns, each 16 ft. high, on its E. side, and has a roof of good cassetted work. The colour of the hieroglyphics and representations is still remarkably vivid in various places, especially in the S. portion near the vestibule of Nectanebus. There appear Nero with his cartouches, Claudius Caesar and Germanicus Autocrator before Horus, Tasentnefert and Pinebtati (who also appears at Ombos, p. 261) worshipping the lord of Ombos. Farther to the N., on the back wall of the colonnade are the name of Tiberius and a fine Greek inscription, beginning (see fig. 8), etc. The translation of the latter is as follows: ‘Ammonius, son of Dionysius , fulfilled a vow made to Isis, Serapis, and the gods worshipped along with them, by presenting to them the worship of his brother Protas and his children, of his brother Niger, his wife Klidemas, and his children Dionysius and Anubas. On the 12th Payni of the 31st year of Caesar’. — This Caesar is Caesar Augustus, in whose reign therefore the wall, though furnished with inscriptions by later emperors, must have existed at least in a rough state. The other inscriptions are of similar purport.19

At the S. end of the E. Colonnade (Pl. D) was a large Hall (PI. C), of which only fragments of the N. and E. walls remain. It bears the name of Tiberius. The colonnade, which adjoins its N. wall, was never entirely completed. Only three of the capitals of the columns (including a very line palm-capital) are finished; the rest are merely roughly blocked out, but they are of interest as showing us that the more elaborate carving was not taken in hand until after the capitals had been placed in position upon the shafts. The E. colonnade does not extend as far as the first pylons, but is separated from them by a small Temple of Æsculapius, the Egyptian Imhotep, son of Ptah (PI. E), consisting of two chambers, and facing the S. The Greek inscription over the entrance dates from Ptolemy V. Epiphanes, his wife, and son, the Egyptian cartouches on the door itself from Ptolemy IV. Philopator (see fig. 9). — The W. colonnade which skirts the river, is joined on the N. by a narrow passage (Pl. a), which leads past the pylons at some distance to the left (W.). The peristyle court, for which fore-court would be a more accurate name, is thus by no means enclosed by the pylons.20

c. The First Pylon (PI. H) turned towards the approaching processions two lofty and broad Towers, with a narrow Portal between them. This portal, built and adorned by Nectanebus II., is the oldest part of the pylon. The smaller portal, to the left, like the temple behind It (Birth-house, see p. 289}, which stands in relation with it, dates from Ptolemy VII. Philometor (see fig. 10); while the decoration of the facade was added by Ptolemy XIII. Neos Dionysus. Within the chief portal appears also Ptolemy X. Soter II., with his mother and wife, presenting to Isis the symbol of a field. The entire imposing erection is 150 ft. broad and 60 ft. high. The S. facade, fronting the processions advancing from the Nile, is covered with Reliefs en creux.21

At each side of the Central Doorway (PI. b) is a figure of Isis. On the upper part of the left tower is the Pharaoh sacrificing to Osiris and Isis, and to Isis and Horus; on the corresponding part of the right tower, he appears before Horus and Nephthys, and before Isis and Horus. The lower parts of the towers are devoted as usual to military scenes. The Pharaoh (Neos Dionysus, 59 B.C.) appears as the smiter of his enemies; to the right, Isis with Hor-hut presents him with the staff of victory. Half of the figures have been deliberately defaced.22

The Ascent of the Pylons, commanding an excellent view of the whole island and its surrounding, is made from the peristyle court entered by the central portal. Within this portal, to the right, is the following lnscription: ‘L’an 6 de la république, le 13 messidor. Une armée francaise commandée par Bonaparte est descendue à Alexandrie. L’armée ayant mis 20 jours après les mammelouks en fuite aux Pyramides, Desaix commandant la première division les a poursuivies au delà des cataractes ou il est arrivé le 13 ventose de l’an 7′ (i.e. March 3, 1799). Then follow the names of the brigadier-generals. — The staircase leading to the top of the *East Tower begins in the small chamber (PI. c), in the S.E. corner of the peristyle court. It ascends gradually, round a square newel. Several unadorned chambers, probably used for the storing of astronomical instruments and for the use of astrologers, are to be found within the tower. They are feebly lighted by window-openings, decreasing in size towards the outside wall. — The West Tower can only be reached from the E. tower. The crosses on the stones of the roof formerly held braces of wood or iron.23

Two Obelisks and two Lions, all of granite, formerly stood before the entrance. The foot of the W. obelisk is all that remains of the former; the latter lie much damaged on the ground. Numerous Greek Inscriptions have been carved here by pilgrims. —Adjoining the S.E. side of the pylon is the beautiful Gateway (PI. G) of Ptolemy II. Philadelphus, who appears on its E. side. On its W. wall, to the right and left, is the emperor Tiberius, above, Philadelphus.24

d. The Inner Peristyle (PI. I), bounded on the S. by Pylon H., is bounded on the N. by another Pylon (PI. K). These, however, are by no means parallel to each other, while the edifices to the E. and W. of the peristyle are so entirely different, that it is at once apparent that the court was not constructed according to any preconceived plan. The requirements of the moment and the available space were taken into account, not any artistic considerations. Nevertheless this court, entirely enclosed by buildings of the most varied forms, must be described as unusually effective. On the E. and W. are two oblong edifices, each with columns on the side next the court. That to the W. (left) is a distinct temple, forming a kind of peripteros; that to the E. was used by the priests. This court, which is mostly uneven, contains one spot excellently adapted for the pitching of a tent. Cook’s parties usually lunch here; if there are more than one party at the same time, the second lunches in the kiosque (Pl. R).25

e. The Temple to the W. of the Peristyle (PI. L) stands immediately behind the left (W.) wing of the first pylon, and a doorway in the latter (p. 287) lies exactly opposite the S. Entrance Door (PI. d) of the temple, from which it is separated only by a narrow open passage. At the N. end of the colonnade on the side of the temple next the court is a side-entrance. The S. door admits to a Pronaos with 4 columns, of which two are engaged in the portal. Beyond lies a Cella with three chambers, surrounded on three sides by a colonnade. This temple was founded by Ptolemy VII. Philometor, and most of its decorations were due to Ptolemy IX. Euergetes II., though the later Lagidae and Tiberius also contributed a share.26

The vestibule here is loftier than the other rooms of the cella. The entrance was adorned by Philometer, but the numerous interior reliefs represent Tiberius before the different deities of the temple. The carefully elaborated doorway at the back of the pronaos dates from Euergetes II. The first room is quite unadorned. Above the door to the second room is a window, bordered on each side by two Hathor-masks. Tiberius is named several times on the walls, which have been partly plastered over with mud. The early Christians, who perhaps used the second room for purposes connected with their services, have entirely plastered over the heathen Inscriptions there; while the highly interesting Representations in the third room have been left quite untouched. From these we learn that the temple was intended to represent the Birth-House or Meshen, in which the infant Horus first saw the light (similar buildings at Denderah, Edfu, etc., pp. 80, 253). The reliefs on the rear wall are in two sections. The lower series represents the Birth of Horus, who is introduced into life by Ammon, Thoth, and other gods. In the upper row we see Horus ascending from a huge bunch of lotus-flowers, and beside him the serpent coiling round a column adorned with lotus-flowers, beneath which kneel two forms, covered with the Uraeus-hood. The allegorical meaning of this latter composition is obscure. On the W. wall of the chamber is a Goddess (head destroyed), offering the breast to the new-born child, and close by is Hathor, the good fairy of Egyptian nurseries, placing her left hand in benediction on the head of Horus, and holding his arm with her right. King Ptolemy IX. Euergetes II. is depicted handing to her two metal-mirrors ‘to rejoice the golden one with the sight of her beautiful form’. — These representations do not only celebrate the mystic birth of the god, they refer also to the most beautiful and most responsible duties of motherhood, which Isis, Hathor, and Nephthys undertake. Their nursling appears indeed to be the infant Horus, but it is evident from many allusions, that the young Pharaoh, the heir to the throne of Ra, was considered as the incarnation in human form of the young god, and that these representations were meant to convey to the Ptolemies that a deity had borne and suckled them or their first-born, and that the immortals had guided their upbringing with invisible hands. Cleopatra I., the mother of the two brothers who caused the placing of this inscription, had acted as guardian and regent especially during the childhood of Philometor, the elder. She was the Isis of the young Horus. On the E. outside wall of the cella a relief shows us Horus learning from the goddess of the N. to play on the nine-stringed lute, while Isis superintends the lesson. The shape of the instrument is Greek, and by the goddess of the north is perhaps meant Hellenic music, which was cultivated even by the earlier Lagidae.27

All the Inscriptions here date from Tiberius, who is named ‘Autokrator Kisres’ on the E. side and ‘Tiberius’ on the W. side. A double votive-inscription of the same date proves that the former phrase applies to Tiberius.28

The columns of the Colonnades on the W. and N. sides of the cella exhibit genuine Ptolemaic capitals with a very high abacus. On the N. side (PI. f) is the peculiar but elegant capital, found only on Philae, consisting of a bunch of papyrus-buds, supporting the abacus on their tips. Screen-walls, more than half as high as the shafts, connect the columns. The most conspicuous columns are the seven on the side of the temple next the court. These have finely sculptured Ptolemaic capitals, surmounted by a cubical abacus with Hathor-masks and chapels. The Architrave above, adorned with the concave cornice and astragal, exhibits an unusually fine inscription, carved in the grand style, of which a duplicate occurs on the architrave of the E. colonnade opposite. This Dedication-Inscription records that Ptolemy IX. Euergetes II. Physkon (with numerous titles) and his wife Cleopatra, princess and mistress of both worlds, the Euergetae (divine benefactors), loved the life-giving Isis, the mistress of Abaton, the queen of the island of Philae (see fig. 11) and the mistress of the S. lands. The king and the queen, Philadelphi (see fig. 12) (divine brothers), Euergetae (see fig. 13), Philopatores, Epiphanes, Eupatores, and Philometores, erected and restored this beautiful monument, that it might be a festal hall for his (the king’s) mother Usert-Hathor, etc., and a scene of joyful excitement, Tekh (see fig. 14), for the mistress of Philae, that she might settle in it, etc. The above list of Ptolemaic surnames is especially important.29

At the top of the left colonnade, next the first pylon, are some demotic and hieroglyphic Decrees, of the 21st year of Ptolemy Epiphanes, one relating to the celebration of the suppression of a revolt and the punishment of the rebels, the other in honour of Cleopatra, wife of Epiphanes. These inscriptions, of great scientific value though extremely lightly and almost illegibly carved, were discovered by Lepsius in 1843. Unfortunately they have been much injured by figures carved over them under Neos Dionysus. An upper story of Nile bricks, now in ruins, was built at some later period on the roof of this peripteral temple. It is entirely out of place and should be removed.30

f. The Building on the E. side of the Peristyle (PI. M), mentioned on p. 288, lies opposite the birth-house, and presents a long Colonnade of 10 columns, with elaborate capitals, towards the court. In the rear-wall of this colonnade is first, to the left, a large doorway, leading through a vestibule to the outside of the temple, and then three lesser doors leading into three small chambers, partly devoted to scientific purposes. At the S. end, close to the pylon, is a fifth door, admitting to a room now half in ruins. To the left of this room is another chamber (PI. 1; see below), and straight on is the Staircase (Fl. m) leading to the rooms on the upper story. Some of the latter are tolerably spacious, but have no inscriptions; whereas the lower story and the columns were adorned with hieroglyphics by Ptolemy XIII. Neos Dionysus. The Inscriptions in the various rooms are due to Tiberius, to whom Philae in general is much indebted.31

The most interesting rooms on the E. side of the peristyle court are first that into which the door nearest the pylon and leading to the staircase admits us, and secondly that to the right of the large doorway. Both are without windows. Inscriptions on the doorposts inform us of the purpose of these rooms. The first (PI. l) was the Laboratory, in which was prepared the excellent incense known as Kyphi, which must have been used in great quantities for the services of the gods. The names and the proportionate quantities (in figures) of the drugs used in its preparation are recorded on the door-posts. The interior has no inscriptions. The other (entered by the fourth door from the pylon) is, on the other hand, very rich in inscriptions. This small room, extremely elegantly adorned with sculptures by the orders of Tiberius (here named ‘Autokrator Kisres’), was the Library (PI. h); and on the right door-post is the legend: ‘This is the library-room (see fig. 15) of the gracious Safekh, goddess of history, the room for preserving the writings of the life-bestowing Isis’.32

The representations over the door must have been specially objectionable to the Christians, for they have all been carefully chiselled out. On the left side of the chamber itself is a recess like a wall-cupboard, in which perhaps the most precious rolls were preserved. Beneath is a life-like relief of a cynocephalus (the sacred animal of Thoth-Hermes) writing a papyrus-scroll. Here as usual the Pharaoh (Tiberius) is depicted receiving the blessings of life in symbols from the deities upon whom he had bestowed gifts; on the right wall he appears before Isis and Horus, on the back-wall before Isis. Between the emperor and the goddess in the latter scene stands an altar, beneath which are two swine, as the sacrificial animals. On the left wall, over the above-mentioned recess, are the sacred ibis of Thoth, Ma, the goddess of truth with the palette and the chisel in her hand, Tefnut, and Safekh; on the door-wall is Khunsu, here named the ‘sacred ibis of Philae’ and thus placed entirely on an equality with Thoth. On the right wall, opposite, is the cow-headed Hest, mother of the gods, with two vessels with handles, before Osiris, Isis, and Horus.33

The next door to the left, higher than the others, leads into a room (PI. g), named ‘Chambre de Tibère’ by Champollion, because Tiberius is represented sacrificing to the gods on both the side-walls and over the door, on the outside, while in the second row on the right he appears again before the Nubian god Arhesnefer (see fig. 16). Above are dedicatory inscriptions by Euergetes II. and Cleopatra his wife, who appear on the door entering from the colonnade.34

Returning once more to the colonnade, we find another door at its N. end (PI. n). Here, an inscription informs us, stood the door-keepers entrusted with the purification of those entering the temple. The lions on the outside wall were also named in an inscription ‘temple-guards’, though symbolically only. — Outside the temple M., in the direction of Bigeh, a Nilometer was discovered by Capt. Handcock in 1886.35

g. The Second Pylon (PI. k), standing at an obtuse angle with the E. colonnade, encloses the peristyle court on the N. It is smaller (105 ft. wide, 40 ft. high) and in poorer preservation than the first pylon. An inner staircase ascends to the W. pylon, whence we proceed across the ruined roof to the E. pylon. To reach the top of the W. pylon, we ascend the staircase to the Osiris-rooms (p. 295), and then proceed leaving these on the right. The ascent of the first pylon (p. 288) is, however, preferable in every respect. On the front of the E. wing facing the peristyle court is a semicircular Stele of reddish brown granite, erected to commemorate a lavish grant of lands, by which Ptolemy VII, Philometor (94 B.C.) enriched the temple. It was inscribed on the polished rear-wall of a monolithic chapel built into the pylon. The king, however, seems merely to have granted to the priests a new lease of the ancient property of the goddess. On the pylon are some Colossal Figures. To the right is King Neos Dionysus holding his enemies by the hair, before Horsiisi and Hathor; beneath, smaller representations. To the left the king appears before Osiris and Isis. The grooves for the flag-staffs should also be noted. The Portal (PI. p) to the temple proper, approached by a shallow flight of steps, was built by Euergetes II. in imitation of the portal of Nectanebus in the first pylon. Within it the predecessors of the builder are recounted.36

The Temple of Isis proper, entered by this portal, was built according to an independent plan, embracing a hypostyle, a pronaos with various divisions, and a sanctuary, with two side-rooms. Ptolemy II. Philadelphus was the founder of this temple, to whose decoration the hostile brothers Philometor and Euergetes II. (Physkon) contributed most largely. It was only natural that both the weak but amiable Philometor and the vicious hut energetic Physkon should interest themselves in the sanctuary of Isis, for both were much interested in retaining Nubia. We are aware that the former maintained a military station to the S. of Philae, which afterwards grew into the town of Parembole (p. 305). Later Ptolemies are also named here. We refrain from a closer examination of the reliefs and inscriptions in this temple, though they are not uninteresting from a mythological point of view, contenting ourselves with a reference to the detailed descriptions of the Ptolemaic temples at Denderah (p. 80) and Edfu (p. 241).37

h. The Hypostyle (Pl. N) contains ten columns arranged in three rows. The second and third rows contain each two columns to the right and two to the left; while the first row has only the two corner-columns, the space between them being left uncovered for the sake of light. The hall thus consists properly speaking of two portions: an uncovered fore-court with two doors, on the right and left, leading to the outside of the temple, and a covered part behind. The columns are 24 1/2 ft. high and 13 3/4 ft. in circumference. The uncovered portion could be shaded from the sun by means of a velarium; the holes for the cords are still visible in the upper part of the concave cornice turned towards the second pylon. The colouring of this hall, which has been preserved on the ceiling and the columns, must have been very brilliant. The Capitals are the most instructive of all the specimens that have come down to us of the manner in which the Egyptians coloured their columns.38

Sky-blue, light-green, and a light and a dark shade of red are the prevailing colours; but these were distributed according to conventional rules. Although vegetable forms are imitated with admirable fidelity, the artists did not shrink from colouring them with complete disregard to nature, simply because ancient convention demanded it. Light-green palm-twigs receive blue ribs, and blue flowers have blue, red, or yellow petals. Below the annuli on the shaft is a kind of band (found also else- where), indicating that the vegetable forms surrounding the core of the capital were supposed to be firmly bound to the top of the shaft. The height and ornamentation of the lower parts of the shafts are the same in all the columns; but the capitals, some of which are beautiful palm-capitals, are varied.39

On the Ceiling are astronomical representations. The entire hall bears the inscriptions of Ptolemy IX. Euergetes II. — Above the door in the back wall leading to the pronaos is a long Inscription, carved over the hieroglyphics by the Italian Expedition of 1841. The Christian successors of the priests of Isis have cut numerous Coptic crosses in the walls to signalize their appropriation of the temple and to guard against the cunning malice of the heathen deities. Christian services were celebrated in this hall. A Greek inscription in the doorway to the pronaos, on the right, records that the good work (probably the plastering up of the reliefs and the preparation of the hall for Christian worship) took place under the abbot Theodorus. This was in the reign of Justinian.40

i. The Chambers of the Pronaos. The three successive rooms of the pronaos date from Ptolemy II. Philadelphus. The First Room (PI. r) was adjoined on each side by others. That on the right, now destroyed, was connected with a Second Room (PI. s), on the E. wall of which Philadelphus is shewn presenting a great offering to his mother Isis. In the room to the left (PI. t), in which the staircase to the roof starts, Philadelphus appears before Isis and before Hathor. The next room to the left is a dark chamber. Eight round the foot of the wall in the following wide Third Room (PI. u), immediately before the sanctuary, runs a list of nomes. The doors on the right and left of this room admit to long, narrow, dark apartments, perhaps used as Treasure-Chambers. The entrance to that on the left (PI. w) is about 2 ft. from the ground. The visitor should enter, strike a light, and inspect the sculptures in this chamber which resembles a huge stone chest. The lower part of the wall is smooth, as it was concealed by the treasures stored here; but higher up Ptolemy II. Philadelphus caused the walls to be adorned with elegant reliefs and inscriptions.41

On the rear-wall is represented Ra enthroned on the symbol of gold (see fig. 17). At the S. end of the W. wall Ptolemy Philadelphus appears kneeling and holding in his arms the large chest of gold, which he presented to the temple of Isis; and the same scene is repeated on the W. wall. In the former case the king wears the crown of Lower Egypt (see fig. 18), in the latter that of Upper Egypt (see fig. 19). — The inscriptions explain that the Pharaoh came to the goddess bringing to her gold to her content, and that the mistress of Philae granted him superabundance of everything, all gifts of plants and fruits that the earth produces, and placed the whole world in contentment. — Similar representations (offerings of bags of gold and bright-coloured garments) occur in the chamber to the right (PI. v), which is in communication with Room s.42

In the ADYTUM (PI. O) is a small Chapel formed of a single stone, with the names of Euergetes I. and Berenice II. (which also occur in the room on the left). But as the inscriptions on the walls attest, this, the oldest part of the inner temple, dates from the time of Ptolemy II. Philadelphus. In the rear-wall of the cella is a crypt. In the room to the right of the adytum is a subterranean floor, with Nile gods and the young prince; above, Philadelphus before Isis and Harpocrates (Horpekhrud).43

k. The Building to the W. of the Hypostyle (PI. P) is reached by quitting the hypostyle by the first floor on the W., (to our left as we enter). It consists of a ruined Cella and a chamber, in fairly good preservation, facing the river. On the S. wall are some remarkable representations. Horus receives the water of life from Isis and Nephthys. The goddess of history behind Isis, and Thoth behind Nephthys write the name of the royal builder on a palm-branch, at the end of which waves the sign of festivals, composed of the hieroglyphs of life, endurance, and power. Ma holds in her hand the sail (see fig. 20), the symbol of new life. Here also is an Isis, who has been converted into a St. Mary. — The handsome Portal (PI. x), built by Hadrian, bears on the right and left, the secret symbols of Osiris. Over the door, to the left, is a small representation of the Island of Philae. On one side appear the cliffs of Bigeh, on the other the pylons of Philae. In a square between these is a highly remarkable relief. At the bottom is a Crocodile hearing on its back the mummy of Osiris, from which flowers spring (comp. the legend of Anas el-Wogûd, p. 281). Above appears the risen Osiris, enthroned with the young Harpocrates, in a disc before which stands Isis. Above the whole the sun appears on the left and the moon to the right, with stars between them; adjacent are a large and two smaller pylons. On the N. wall, close to the room lying nearest the river, is the famous Representation of the Source of the Nile (see fig. 20), already mentioned in Vol. I., p. 135. Bigeh (Senem), one of the cataract islands, is here depicted, with a cave in its lowest part. In this crouches the Nile, guarded by a serpent, and pouring water from two vases. On the summit of the rocky source of the waters are a vulture (Muth) and a hawk (Horus), gazing into the distance and keeping watch. This is almost the only landscape hitherto discovered on any Egyptian monument. The inscription is in these words: ‘the very remote and very sacred, who rises in Bigeh (Senem)’.44

On the front of this little temple, to the left, is a Demotic Inscription in red letters, in which Aurelius Antoninus Pius and Lucius Verus are mentioned with their titles derived from conquered provinces. The Cartouches of these late emperors occur also on the walls of the temple; and on the outside of the W. wall are numerous inscriptions, chiefly demotic.45

1. The great Outside Walls of the Temple are covered with Inscriptions; to the left (W.) by Tiberius, to the right (E.) by Autokrator Kisres (perhaps Augustus or even Tiberius again). The most noteworthy is a List of Nomes, of great importance for the geography of the ancient Egyptians (Vol. I., p. 31). On the W. wall are the nomes of Lower Egypt, on the E. wall, near the foot, those of Upper Egypt. Other lists are found within the temple.46

m. The *Osiris Room, remarkably interesting on account of the sculptures which cover its walls, is found as follows. Returning to the second room (PI. t) of the pronaos we pass through the door on its W. side (next the Nile), and immediately to the right see a Portal (still in the temple), leading to a Staircase which we ascend. A second staircase then leads to the roof of the cella. Here we turn towards the S. and finally descend some stone steps to a doorway built over with Nile bricks. The Vestibule is interesting. Hapi (the Nile) lets milk trickle from his breast and Horus pours the water of life (see fig. 22), over Osiris, who lies in the shape of a mummy upon a bier. Twenty-eight lotus-plants sprout from him, referring perhaps to the 28 days of the month, or the 28 ells of the maximum height of the Nile at Elephantine, or to the 14 scattered and reunited parts of his body.47

The ‘sprouting’ of the dead into new life is a conception frequently made use of, even with regard to the passing away of mankind. In the Book of the Dead are the passages ‘I have accomplished the great path (in the boat of the sun), my flesh sprouts’, ‘He has become a god forever, after his flesh acquired quickening power in the underworld’.48

At the resurrection of Osiris all the spirits are present who play a part in the Egyptian doctrine of immortality. They here appear in long rows on the walls of the sacred chamber. The risen Osiris is adorned with all the insignia of his dignity as a ruler of the underworld.49

On the left door-post of the Osiris room are three Greek Inscriptions, of which the longest dates from the 165th year of Diocletian (449 A.D.) and another (very short) from the 169th year of Diocletian (453 A.D.). From these it is evident that the pagan worship of Isis and Osiris was practised [sic.] here down to a late period. The votive inscriptions were composed by the proto-stolistes Smetkhen and his brother Smet.50

A few smaller edifices still remain to be visited. To the N. are the ruins of a Christian Church, into which have been built fragments of an earlier structure of Tiberius. Here also is an inverted Naos, dating from Ptolemy and Cleopatra. —If we quit the hypostyle of the temple of Isis proper by the small portal in its E. wall between the first row of columns and the second pylon, we see about 50 paces in front of us the Chapel of Hathor (PI. Q), the smallest temple on the island. That it was especially dedicated to Hathor we learn from hieroglyphic inscriptions (see fig. 23) of the time of the emperor Augustus, and from the Greek inscription (see fig. 24), ‘Hiertia directed (a prayer) to Aphrodite (Hathor)’.51 The fact that the rear wall of this chapel has no inscriptions and the ruins behind it indicate that it was once joined to some larger edifice. At the entrance stand two Ptolemaic columns, with a doorway between them, the side-posts of which, unconnected with each other at the top, reach to the bands below the capitals. This doorway is built up, and it is probable that the single apartment within the temple was used as a dwelling, as its walls are much blackened.52

Within appear Ptolemy VII. Philometor and Euergetes II. with Cleopatra; and also over the entrance. On the S. side is the emperor before Hathor and Horsamtani, and before Khnum and Hathor; on the N. side before Osiris and Isis. Beneath was a geographical inscription.53

The Kiosque.

A few minutes bring us from the chapel of Hathor to the elegant and airy Pavilion (PI. R), frequently called ‘Pharaoh’s Bed’, one of the chief decorations of the island, which may be easily recognized by the lofti abaci, or rather imposts, that support the architrave. Passengers are usually landed immediately below it. It is situated on the E. coast of Philae, which is here bounded by a carefully built wall. The builder of this beautiful temple, dedicated likewise to Isis, was Nerva Trajanus; but its ornamentation with sculptures and inscriptions was never quite completed. The inscriptions contain little of importance, so that the visitor may resign himself at once to the pleasure of rest and luncheon on this beautiful spot. The Kiosque of Philae has been depicted a thousand times, and the slender and graceful form, that greets the eyes of the travellers as they approach the island, well deserves the honour. The architect who designed it was no stranger to Greek art, and this pavilion, standing among the purely Egyptian temples around it, produces the effect of a line of Homer among hieroglyphic inscriptions, or of a naturally growing tree among artificially trimmed hedges. We here perceive that a beautiful fundamental idea has power to distract the attention from deficiencies in the details by which it is carried out. Although exception may be taken to the height of the abaci and to many other points, no one who has visited Philae will forget this little temple, least of all if he have seen it by moonlight.54

In the N.E. of the island are the ruins of a village and of buildings of various kinds. In the extreme N.E. is a Roman Triumphal Arch (PI. 8), with a lofty middle portal flanked by lower wings. The structure, which has also been taken for a city-gate, faces the E., i.e. the well-fortified bank of the Nile. The S. wing is in good preservation but is somewhat clumsy. Above it is a brick dome supported on sandstone consoles. It is possible that Diocletian passed beneath the central arch when he visited the sacred island of Philae. His name, at all events, is to be found on the blocks of sandstone scattered on the ground.55

The huge heaps of ruins scattered over the island defy description, and contain little of interest. On the other hand study may well be devoted to the numerous Inscriptions in demotic, Greek, Latin, Coptic, and Arabic. Some of the Greek inscriptions are elegant. The Verses of Catilius surnamed Nicanor, son of Nicanor, who lived 7 B.C., are excellent; and his acrostics display considerable skill.56

The Cataract Islands.

The islands in the neighbourhood of Philae are picturesque, but a visit to them can be recommended only to Ægyptologists and geologists, for they contain nothing but rocks with a few inscriptions carved upon them.57

Bigeh, called by the ancient Egyptians Senem-t (see. Fig. 25), lying opposite Philae, is the most easily accessible. It is reached in about two minutes from Philae, of which it commands a picturesque view, as Philae does of it, with its bare rocks and ruined buildings. Bigeh enjoyed a very early reputation for peculiar sanctity, and we have already seen (p. 294) that one of the symbolical sources of the Nile was located here. Various Rock Inscriptions and also the hieroglyphics on a granite Statue of Osiris found here record that as early as the 18th Dyn., under Amenhotep II. and Amenhotep III., this island was visited by pilgrims and was provided with temples. The deities chiefly worshipped in the latter were the ram’s-headed Khnum, god of the cataracts, and a Hathor. Senem was not regarded as belonging to Egypt but to Kush, i.e. Ethiopia, or Ta-kens, with which the modern Kenûs may be compared. Among the pilgrims, whose names are found on Bigeh, were several governors of Ethiopia, who were usually royal princes. The ruins of the Temple visible from Philae, in which the name of Ptolemy Neos Dionysus is of most frequent occurrence, are now inhabited by an obliging Nubian family, only a few of whose members understand anything but Kenûs. The most interesting remains here are Two Columns, with unsculptured Ptolemaic capitals and a Portal with a carefully built arch, adorned with a Greek ornament. Adjoining the latter is a House built of bricks, Nile-mud, and broken stones, in which is a stele with figures of Horus and Isis, Khnum and Sekhet. Behind the temple is a well executed Colossus of Amenhotep II. (18th Dyn.), ‘the beloved of the mistress of Senem (Bigeh)’, treading upon the nine bows, i.e. the barbarous tribes. Kha-em-us, the favourite son of Ramses II., visited this island and recorded the festivals of his father. Dignified officials of the 26th Dyn. celebrated themselves and their princes (Psammetikh II., Hophra, Aahmes) in brief inscriptions cut in the hard stone. At a later date Philae superseded the rocky Bigeh as a pilgrim-resort.58

The island of Konosso (called by ancients Ḳeb-t (see fig. 26)), whose name seems to be connected with Kush and Kenûs, also contains numerous Rock Inscriptions some dating as far back as the 11th and 12th Dynasties. Several long inscriptions of the 18th Dyn. have been preserved. One of 13 lines celebrates the victory of Amenhotep III., represented in the colossi of Memnon, over the Kushites or Ethiopians. Konosso was also visited by pilgrims down to the 26th Dynasty.59

The island of Sehêl, which contains many peculiar kinds of stone, may be reached by the dhahabîyehs. Its rugged rocks abound with inscriptions, mostly of the 18th and 19th Dyn., though the earliest date from the 13th, while a few were inscribed under the 20th and 21st. This island was specially dedicated to the cataract-god Khnum and to the goddesses Anuke and Sati.60

- Baedeker 1892, 281. ↩

- This meaning belongs to the old Egyptian root lek, which is preserved in the Coptic Ⲗⲱϫ. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 281. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 281-2. In the Thousand and One Nights this tale occupies the 371st to the 380th nights. It differs considerably from the versions of the sailors, which moreover vary very much among themselves. The tale of Anas el-Wogûd and his mistress El-Ward (‘the Rose’) is the title of a lithographed pamphlet of 34 leaves in which the above story is narrated in verse in the fellâḥin dialect (not the literary Arabic). With several other pieces, e.g. the ‘Cat and the Rats’, it supplies the usual material for recitations in the Arab coffee-houses, and is thus universally known. It begins ‘I shall build for thee a castle in the midst of the sea (i.e. water) of Kenûs, i.e. Nubia. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 282. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 282. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 282-3. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 283. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 283-4. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 284. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 284. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 284. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 284-5. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 285. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 285. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 285-6. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 286. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 286. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 286-7. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 287. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 287. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 287-8. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 288. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 288. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 288. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 288-9. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 289. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 289. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 289-90. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 290. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 290. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 290-1. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 291. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 291. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 291. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 291-2. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 292. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 292. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 293. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 293. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 293. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 293-4. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 294. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 294-5. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 295. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 295. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 295. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 295. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 295. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 295. ↩

- After ἐποίησεν the word εὐχήν is probably to be inserted. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 295-6. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 296. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 296-7. ↩

- The following words have been deciphered: ΔΙΟΚΛΗΤΙΑΝΟΝΕΡλΟΝΚωΝΣΤΑΝΤΙ ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 297. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 297. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 297-8. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 298. ↩

- Baedeker 1892, 298. ↩